In response to the COVID-19 pandemic having led to widespread unemployment and economic recession, the federal government stepped in to provide relief funds to local governments across the country. These funds presented an unprecedented opportunity to pursue an inclusive and equitable economic recovery.

But because COVID-19 recovery dollars offered many more direct and flexible funds to cities (PDF) than had been offered during previous recessions, local leaders had little experience allocating resources of this scale in such a short time period.

In our new study, we examine the processes by which three regions decided to spend their American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) flexible federal recovery dollars and compare their processes with best practices from the literature on inclusive and equitable spending.

In this blog post, we show how and to which sectors the cities allocated their money. Through our analysis, we find that localities that pursued strategies foregrounding community engagement, data, and equity were more likely to allocate ARPA dollars toward equitable recovery strategies.

Memphis, Tennessee: A top-down approach

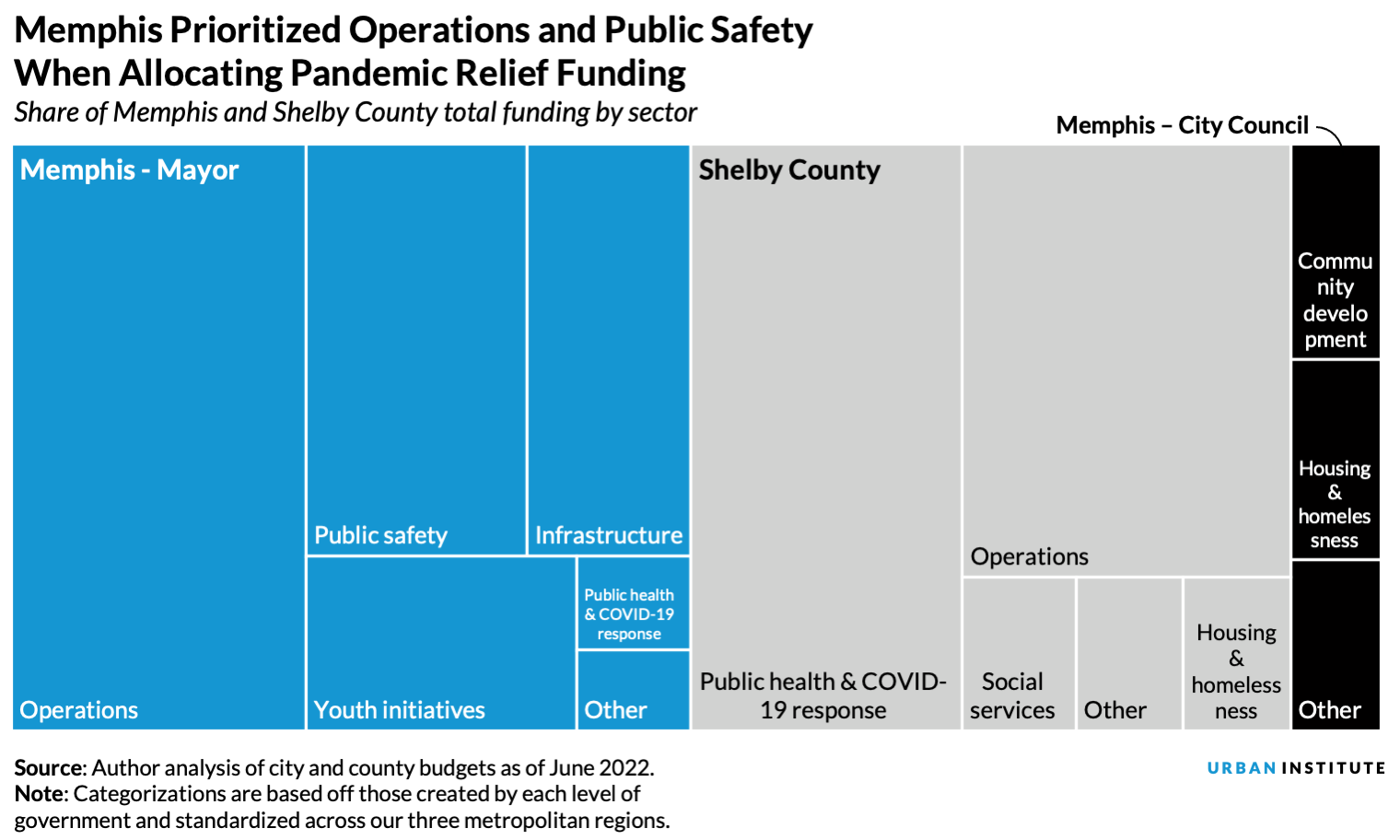

Memphis and Shelby County received $298 million in federal recovery dollars, which they allocated quickly but without a robust community engagement strategy or equitable allocation processes.

Government leaders didn’t require written requests for proposals or provide clear selection criteria for funding recipients. Additionally, the community had little opportunity to provide input other than public council meetings, which had low attendance.

This top-down approach directed little of the money toward equity investments. The majority of both the city and county’s funds (73 percent) went to operational budget gaps, revenue replacement, emergency public health response, and public safety. Public safety received a lot of attention: 12 percent of the full allocation went to public safety initiatives, compared with 5 percent for homelessness and housing initiatives. One person who works at a local nonprofit believed this prioritization reflects the area’s politics. “You get elected in Memphis talking about crime,” the interviewee said. “So the default is always ‘police first.’”

A smaller share of funds went to community needs, such as social services, transitional housing, and vaccination efforts. The funding that did go toward community needs was funneled to larger, more-established organizations that could demonstrate tried-and-true interventions, rather than to innovative pilots.

Nearly half (44 percent) of the total city budget allocated to youth programming went to just one organization, the Boys and Girls Club. Allocating funds only to larger organizations with the capacity to produce an evidence base for their services helps ensure the money is used effectively, but it can also preclude smaller organizations and innovative, new ideas from receiving funding.

Rochester, New York: Disjointed process, disjointed results

In the City of Rochester and Monroe County, efforts were made to establish equitable processes and center resident priorities, but neither locality fully followed best practices to carry out these plans. Although the county conducted more well-rounded community engagement efforts than the city, interviewees noted a lack of transparency as the county allocated funds. Despite limited community engagement, the city employed stronger equity mechanisms within its allocation process by using a budget equity tool and an ARPA spending dashboard.

Both jurisdictions focused on economic development—which comprises the largest allocation bucket for the county (26 percent) and the third-largest for the city (11 percent)—and public safety and social services. But otherwise, the city and county largely deviated in their allocations.

The city’s highest allocation category was housing (23 percent), which only comprised a small share of the county’s allocations (3 percent). The county also dedicated 16 percent of its funding to public health, while the city dedicated a comparable amount toward infrastructure (15 percent).

These allocations demonstrate some degree of responsiveness to the community needs expressed through the jurisdictions’ engagement efforts. But interviewees noted that the city and county didn’t fully coordinate their expenditures and that greater collaboration, particularly regarding economic development and housing, would’ve likely led to more equitable outcomes. With significant ARPA funds yet to be allocated, both the city and county can still leverage their combined recovery awards to invest in large-scale, community-aligned projects.

Chicago, Illinois: Weighing historic harms with emerging needs

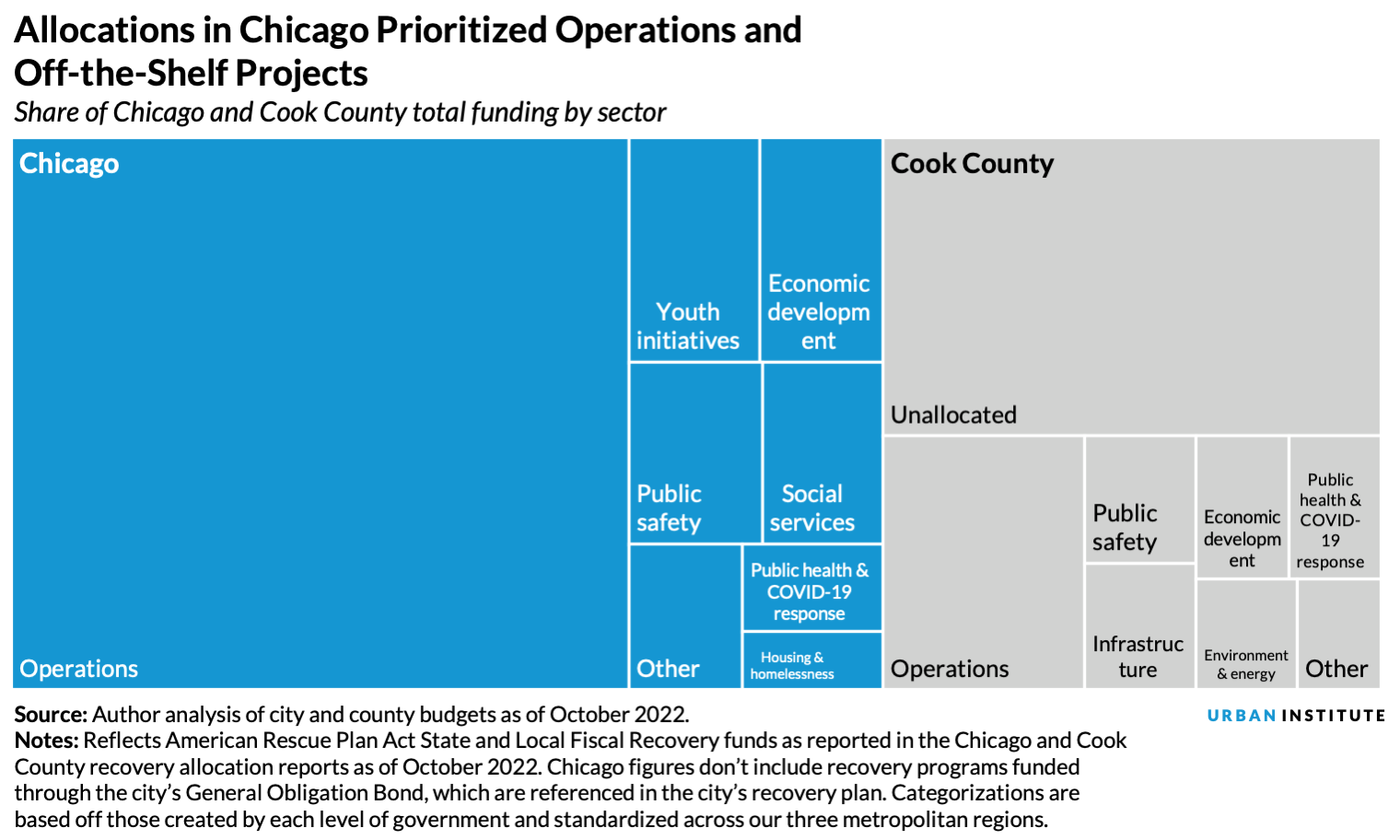

In Chicago and Cook County, Illinois, the jurisdictions took different approaches to incorporating public feedback. Although both jurisdictions held feedback sessions, Cook County supplemented these meetings with online surveys and door-to-door engagement, while Chicago convened with local organizations, faith leaders, and other stakeholders representing communities’ interests.

To ensure investments were equity driven, both jurisdictions prioritized funds in areas with lower degrees of historical investment, including Chicago’s South and West Sides and Cook County’s South Suburbs. Cook County also embedded equity in their evaluation criteria, requiring proposals to identify equity implications and assessing ideas through an equity scoring rubric.

Although both jurisdictions demonstrated interest in pursuing innovative programs, constraints such as staffing, time, and procurement requirements limited their ability to develop new programming. In Chicago, quick implementation plans were prioritized as a result, but bureaucratic barriers slowed some of these programs.

Ultimately, Chicago allocated the majority of its funds toward operations for core services and personnel but also used a substantial $660 million general obligation bond to supplement funding for other recovery priorities. In the county, the largest share of funds remains unallocated, but operations has the current highest allocation (15.5 percent).

Of the regions studied, Chicago and Cook County were the only localities to invest in explicit environmental projects, with Chicago primarily funding these programs through its bond and Cook County funding them through 3 percent of its ARPA funds. Although these investments are small, they signal an understanding of the relationship between climate justice and advancing equity more broadly.

How localities can better incorporate equity considerations in spending

Based on these case studies, we’ve identified three ways local governments can more equitably and inclusively allocate funds:

- Invest in long-term community engagement. By having dedicated community engagement staff who build relationships with community members not only in times of crises but continually, local governments can earn community trust and develop more equitable spending practices. This engagement should prioritize people with low incomes and people of color to uplift the voices of those without historical power and opportunity.

- Make evidence-based decisions. Leaders shouldn’t only consider using prior evidence to inform decisions about investments but should also fund promising smaller organizations and practices that may lack a history of evidence but that represent the interests of historically underrepresented people. Leaders can also work to fill demographic data gaps to understand how proposed investments can affect equity.

- Embed equity as an evaluation criteria. Governments should center equity by using data on who might benefit from investments to make decisions and offering transparency around decisionmaking criteria and spending.

Let’s build a future where everyone, everywhere has the opportunity and power to thrive

Urban is more determined than ever to partner with changemakers to unlock opportunities that give people across the country a fair shot at reaching their fullest potential. Invest in Urban to power this type of work.