Housing costs have grown rapidly over the past few years in the US. In cities like Chicago, this phenomenon has been acute—the cost of the median home rose 40 percent more quickly than incomes between 1990 and 2022. And these changes have not been felt equally. Black Chicagoans experienced a decline in homeownership by 3 percentage points between 1990 and 2020, while a substantially higher share of Black renters are now cost-burdened.

In this post, part of a broader collaboration with the Metropolitan Planning Council, I investigate how housing supply has contributed to these racial housing gaps. One potential mechanism I explore is the effects of zoning policies, which play a role in dictating where new homes are built—and thus affect housing costs. I find that in Chicago, restrictive zoning, combined with substantial variation in market demand for new construction, has created a tale of three cities—a set of conditions all too common across much of the US:

- Construction is disproportionately located in and near downtown, in high-density buildings.

- Well-resourced neighborhoods outside downtown with a high share of white residents and high market demand have used restrictive zoning to limit the construction of housing, which likely contributes to the city’s patterns of racial and economic segregation.

- Other nondowntown neighborhoods that have suffered from historic disinvestment and high rates of poverty have space to build but haven’t received much new construction because of low developer interest.

To counter these conditions, Chicago can alter zoning policies to add housing in high-opportunity areas while expanding support to communities facing historic underinvestment.

Examining urban development in Chicago

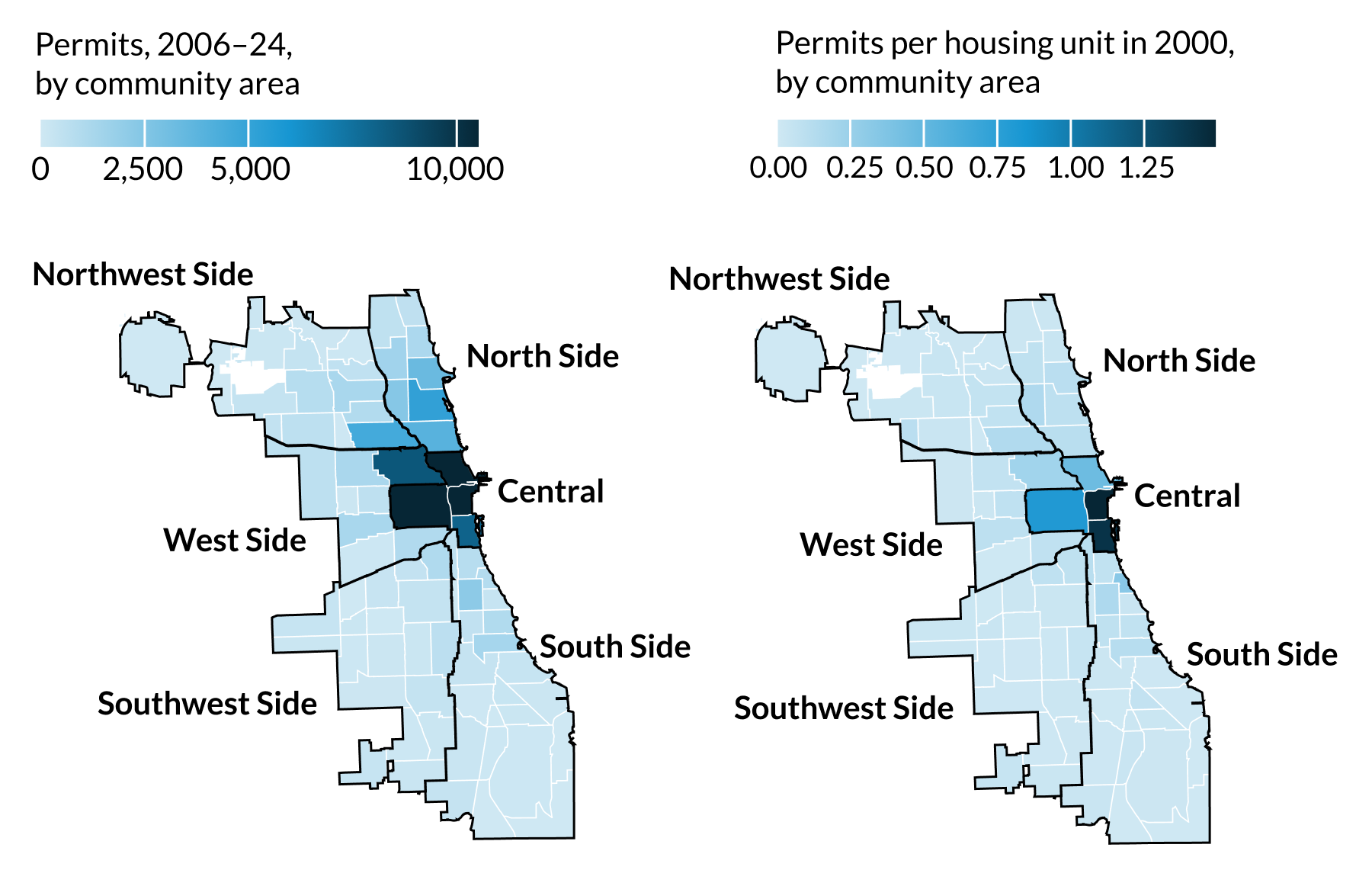

Before building, developers must apply for permission from the local government, which ensures plans’ congruence with zoning and building codes. Using city permitting data, I identified more than 120,000 planned housing units between 2006 and 2024 and compared their locations with zoning and demographic data.

Residential permits weren’t evenly distributed throughout Chicago. More than 50 percent were in the city’s central area, including the Loop and the Near North, Near West, and Near South Sides. In particular, buildings with 50 or more housing units were concentrated in this zone, with more than 75 percent of all such permitted units located downtown. In the Loop and the Near South Side, the number of units permitted more than doubled the baseline housing supply in 2000.

Outside of the central area, much of the rest of the city experienced almost no housing development. Of the city’s 77 community areas, only 10 areas outside downtown had more than 1 unit permitted for every 10 housing units it had in 2000.

Sources: Author’s calculations, based on an analysis of City of Chicago open data (2006–24), the 2000 US Census, and US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey five-year data (2018–22).

Zoning and demographics influence where housing construction occurs

Why was permitting concentrated downtown, which accounted for less than 8 percent of the city’s housing in 2000 and only 5 percent of its land? One explanation is the downtown area’s relatively permissive zoning. More than 16 percent of land in that area was zoned for high densities (defined as buildings with allowed floor areas more than 5 times that of their lot size), far higher than elsewhere in the city, where such ratios typically sit at 2 or below. Another is market demand—the center’s housing values were substantially higher than the city’s overall.

However, the rest of the city still experienced lower-than-expected permitting, given land area and preexisting housing units. The North and Northwest Sides accounted for 24 percent of the city’s permitted units, even though they had 40 percent of the city’s homes in 2000. This permitting underperformance happened despite the high demand to live in these pricey neighborhoods, which also have high white population shares.

Zoning may be blocking construction in those areas. On the Northwest Side, most land is zoned to allow only one- or two-family homes to be built. And on the North Side, just 2 percent of land allows construction of high-density multifamily buildings. These are high-opportunity neighborhoods, where schools boast higher test scores and where grocery stores are easier to come by. But the city’s zoning choices may prevent these communities from accommodating a greater diversity of residents.

Housing permitting also underperforms preexisting conditions on the South, Southwest, and West Sides. In these cases, limited market demand, indicated by low housing values, is likely the biggest obstacle to development. Current zoning, while limiting in some ways, nonetheless allows for more construction, given the high number of empty lots in the area.

Our research shows that thousands of additional housing units could be built in those neighborhoods, yet developers are reluctant to do so because they believe they are less likely to profit. There may also be a racial element at play. Fewer than 35 percent of units permitted citywide were in community areas where a minority of residents are white, which make up 75 percent of the city.

These neighborhoods suffer from historic underinvestment and high levels of vacancy, and the limited construction reinforces that pattern of inequity. Opposite sides of the city feature vastly different living conditions. One side has high levels of wealth, while the other has high levels of vacancy.

Is there a way out of the three-city development morass?

There is nothing wrong with the high rate of housing development in central Chicago. This area has the best public transportation options and offers access to jobs and other opportunities. But Chicago residents also want options to live elsewhere in the city.

Zoning rules—set by city councilors—are likely preventing new construction on the North and Northwest Sides, which keeps home prices high and prevents new people from moving in. And low market demand limits developer interest in building in much of the West and South Sides.

Policymakers should consider several key approaches to promote construction citywide, not only in Chicago but also in other cities that face similar development conditions:

- Enable more permissive zoning in well-resourced neighborhoods outside of downtown. Many communities restrict development to all but one- or two-family homes, complicating the construction of more affordable apartments. Cities like Spokane allow six-unit homes, which used to be constructed often in Chicago, to be built almost everywhere.

- Allow developers of subsidized affordable housing to circumvent zoning restrictions in certain neighborhoods. The city’s new social housing fund offers developers a new incentive to build affordable housing, but these units cannot reach their full potential unless they enable families with low incomes to live in opportunity areas. Massachusetts allows developers of affordable units to override local zoning in some cases.

- Support new investment in historically low-income communities. Chicago already funds a successful, if limited, program for businesses to do so. The US Congress could support such initiatives through the passage of legislation that rewards private investment in lower-income communities. The city can also focus more of its public placemaking and infrastructure spending in low-income areas.

Let’s build a future where everyone, everywhere has the opportunity and power to thrive

Urban is more determined than ever to partner with changemakers to unlock opportunities that give people across the country a fair shot at reaching their fullest potential. Invest in Urban to power this type of work.