View the Spanish version of this post.

With many Americans finding newfound freedom to travel while on the clock because of remote work policies, some have found an ideal destination in Mexico City. The city’s vibrancy, relative affordability, and proximity to the United States have all attracted these remote workers. In 2022, the number of US nationals receiving a Mexican temporary resident visa increased 84 percent compared with 2019.

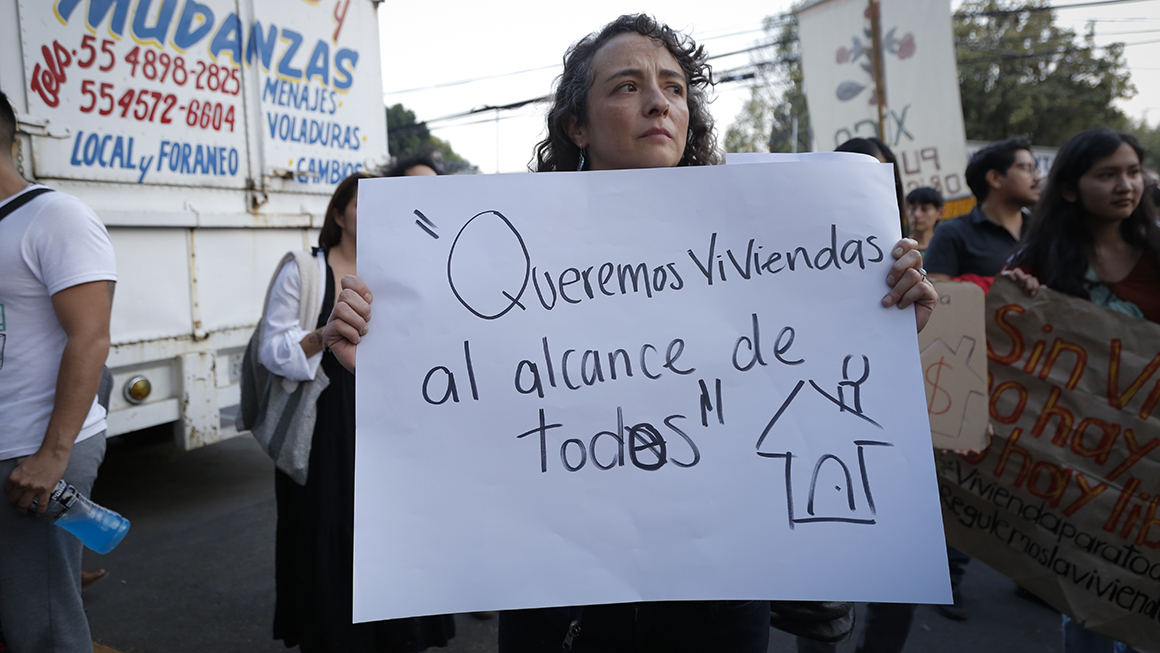

According to Airbnb, digital nomads spent around US $467 million in Mexico City in 2021, mostly on the hospitality industry, equal to 15 percent of the city’s tourism sector’s annual income. Many of these digital nomads established themselves in the city’s central neighborhoods, which have the best access to public services. But to make space for these visitors, many property owners are converting their units in the long-term rental and for-sale markets to short-term rentals (STRs), pushing local residents out in the process. These visitors’ higher purchasing power is also reportedly contributing to increases in housing costs for residents, a process that’s been documented in other cities that have experienced an increase in the use of STRs.

Unlike immigrants, digital nomads don’t pay income taxes to their host countries because they’re still employed abroad, limiting their fiscal contributions to sales taxes and hospitality taxes (5 percent of the total lodging price in Mexico City). For Mexican states and municipalities, which rank among the lowest in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries in terms of tax collections, this absence of revenue can be crushing.

For Mexico City to increase its fiscal resources, address its critical housing challenges, and contain some of the negative effects of abundant STRs, it can create policies that discourage property owners from converting their units to STRs and increase taxation in the market.

How other global cities are addressing the negative effects of short-term rentals

Mexico City isn’t the only place that’s been affected by an ever-expanding STR market. Other localities across the world have aimed to discourage property owners from converting housing units in the long-term leasing and for-sale markets to STRs and increase tax collection from foreign visitors through new programs and policies.

Although the below examples have yet to prove their effectiveness, they all target the key mechanism by which STRs increase rents: reducing housing stock in the long-term rental and for-sale markets.

- Paris, France, limits the number of days an STR host can rent their property to 120 days. Hosts are also required to register their property if it’s rented in its entirety (as opposed to a room or section of a property). The measure has the explicit purpose of tackling housing shortages in the city.

- New York City is working through a plan to ban rentals of entire dwelling units through STR platforms. Similar to Paris, this measure aims to address local housing shortages, especially because recent reports claim there are more Airbnb listings than apartments for rent in the city.

- Italian municipalities have tourist taxes, which are set at different levels depending on the location, the time of the year, and the type of accommodation. The tax is waived for residents. Other countries and regions also have taxes targeted at foreign tourists.

What an STR reform could look like in Mexico City

To prevent more housing units to be turned into STRs, Mexico City could limit the number of days an STR host can rent an entire property. Single rooms within a property could be exempted from this cap, which officials could set to 60 or 90 days. These rules may discourage property owners from converting their units to STRs while allowing owners with available rooms to still have access to alternative income sources.

The city could also impose an additional tax through STR platforms when guests pay with a foreign credit or debit card and for reservations of more than 31 days. Alternatively, it could impose a general tax that’s exempted when guests use a national card (like Italy’s tourism taxes). The latter approach could help avoid legal constraints around discriminatory taxation.

Although Mexico City has already set up a small tax for lodging, it has room to increase how much it taxes STRs. Honolulu has an almost-14 percent Transient Accommodations Tax, for example. These types of initiatives are only effective when coupled with decisive enforcement policies, but introducing these initiatives could itself incentivize property owners, hosts, and renters to protect local communities.

These policies must prove they can reduce, or at least contain, housing costs. If implemented, Mexico City would need to establish effective evaluation efforts. Regardless, monitoring how rents and housing prices evolve in relation to residents’ wages and incomes, and understanding who wins and who loses from an expansion in STRs, will be critical for effective policymaking.

Digital nomads can stimulate local economies through consumption of goods and services, and, if turned into long-term residents, they could integrate into the local labor force and entrepreneurial networks, potentially enriching economies and boosting innovation. But in the short term, cities need to ensure that more STRs don’t drive prices out of current residents’ affordability. Effective STR regulations could help stabilize housing prices and ensure that digital nomads appropriately contribute to the places and communities that welcome them.

Let’s build a future where everyone, everywhere has the opportunity and power to thrive

Urban is more determined than ever to partner with changemakers to unlock opportunities that give people across the country a fair shot at reaching their fullest potential. Invest in Urban to power this type of work.