For months, headlines have blared that the Federal Reserve is tightening monetary policy to fight inflation. That has meant multiple rate hikes and portfolio reductions, with forward guidance communicating more actions to come.

Since March 2022, the Federal Reserve has raised the federal funds rate from 0.25 to 0.50 percent to 3.00 to 3.25 percent. Market expectations, which are conditioned on Federal Reserve guidance, indicate that two more interest rate hikes are expected by the end of the year: 75 basis points in November and 50 basis points in December. The Federal Reserve has also reduced the size of its securities portfolio by allowing both mortgage and US Treasury securities to run off. The portfolio reductions began in June; starting in September, the Fed will allow up to $60 billion of Treasury securities and up to $35 billion of mortgage securities to run off each month.

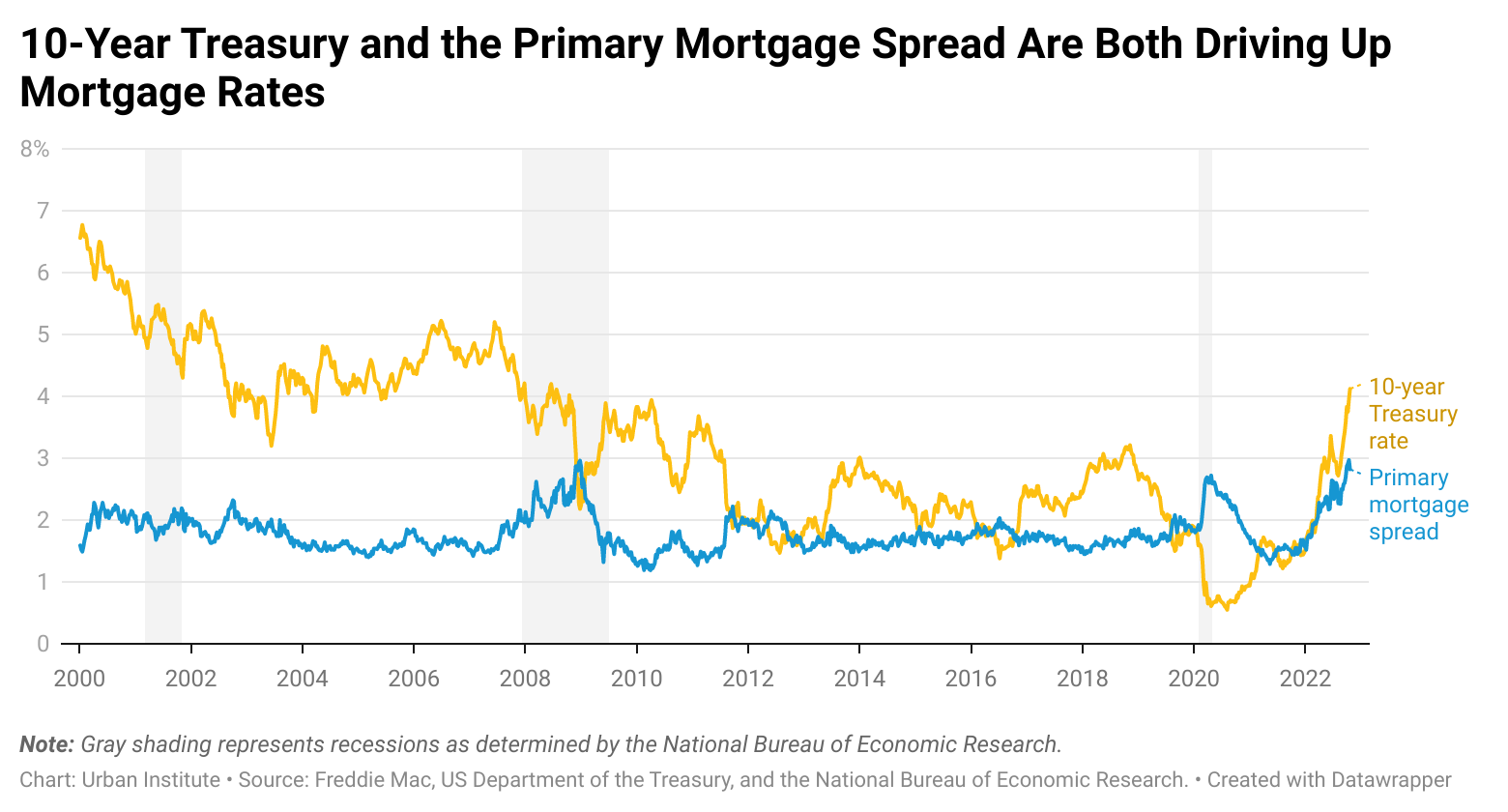

The result is that market rates are up dramatically this year. The 10-year Treasury rate has risen from 1.43 percent in late 2021 to 4.08 percent for the week ending October 20, 2022, a 265 basis-point increase. And the rate on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages has increased 383 basis points from 3.11 percent in late 2021 to 6.94 percent for the week ending October 20, 44 percent more than the Treasury rate increase.

With these dramatic rate hikes, the “mortgage spread”—or the difference between the rate on 30-year fixed-rate amortizing mortgages and 10-year Treasury notes, two instruments with comparable price sensitivity—has widened considerably. In fact, mortgage spreads have surpassed the difference of those present during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and are approaching levels last seen during the 2008 financial crisis. If mortgage rates had risen the same amount as Treasury rates, the current mortgage rate would be well under 6 percent rather than pushing 7 percent.

Why the widening in mortgage spreads?

To understand why the mortgage spread has increased, we first need to rule out some basic explanations. Because most mortgages are either government-guaranteed or government-sponsored and the Federal Housing Administration, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac have not changed their insurance or guarantee fees, we know that the rise in mortgage rates is not because of fears of home price depreciation or borrower default. Credit concerns don’t apply to most of the rest of the market either, as it is composed largely of high-quality bank portfolio loans that generally require large down payments.

A small amount of the additional spread reflects the higher costs lenders face—origination volume is down, so fixed costs are spread over a smaller number of loans—but the primary reason for the spread widening is the increase in interest rate risk. The uncertainty about the effects of Fed policy to date and about the trajectory of future policy has resulted in large movements in interest rates. These large rate movements negatively affect mortgage investors. As rates rise, mortgages experience lower prepayment rates and are outstanding longer, leading to larger price decreases. As rates fall, prepayments increase and the mortgages shorten, leading to lower price increases.

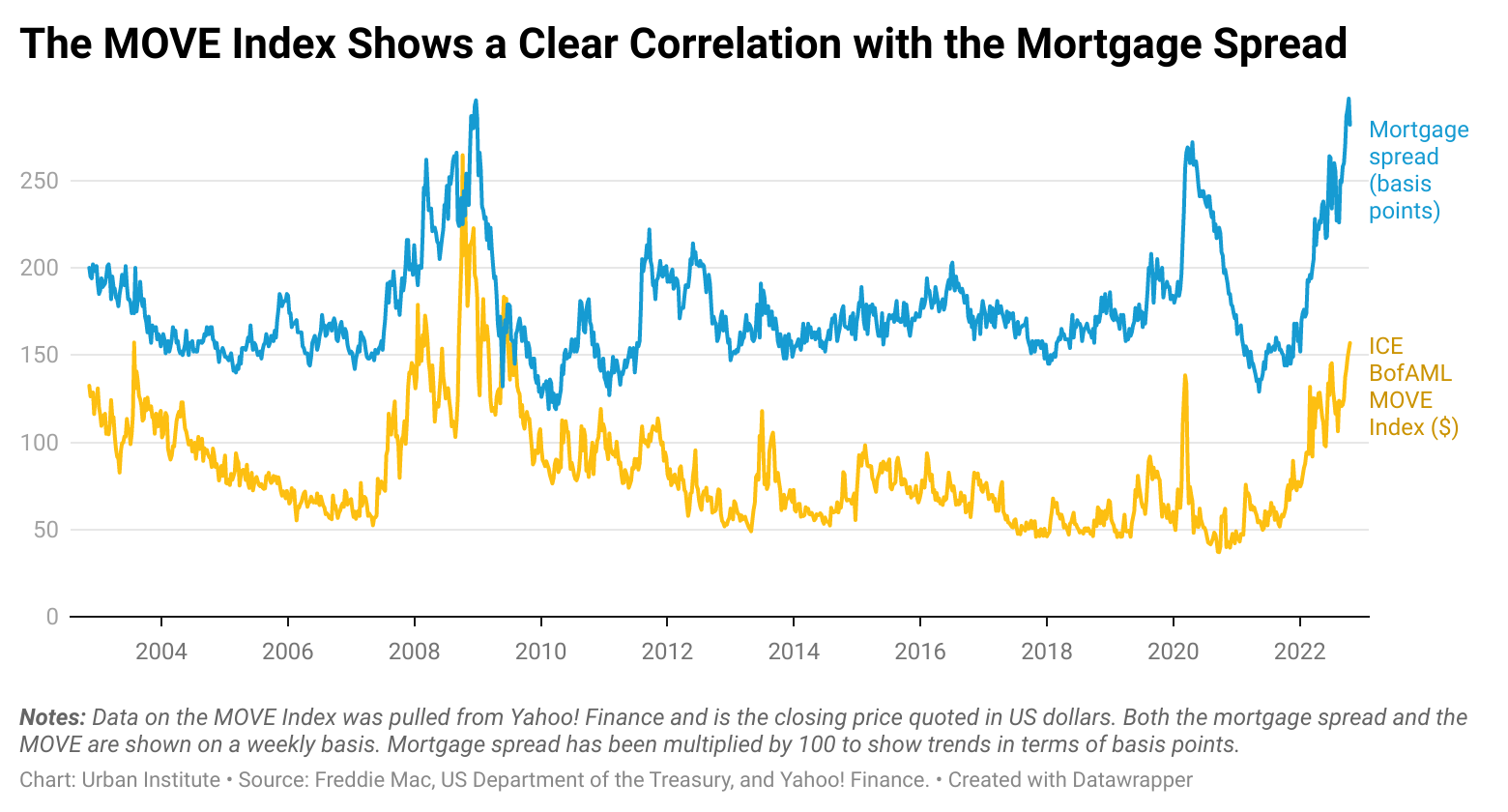

Supporting this reasoning is the relationship between the MOVE index, which is the best-recognized index of interest rate volatility, and the mortgage spread. The MOVE index measures the level of yield volatility implied by the prices of one-month, over-the-counter options on 2-year, 5-year, 10-year, and 30-year Treasury notes. Currently, the MOVE index is higher than it has been at any point since the financial crisis.

The relationship between the MOVE index and the mortgage spread also shows that both of the previous instances of spread widening (the financial crisis and the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic) were characterized by falling rates and large increases in the MOVE index.

Since the mortgage spread has increased so dramatically because of interest rate volatility, not credit fears, we would expect corporate spreads to have increased far less than mortgage spreads, which has been the case. At the peak of the financial crisis, only the highest-rated corporate borrowers (AAA rated) paid a lower spread and a lower interest rate than mortgage borrowers. Now, all but the weakest corporate borrowers (BA rated) are paying a lower spread and a lower rate overall than mortgage borrowers.

Implications of a widening mortgage spread

Today’s high mortgage rates are an important reminder of the role Treasury rates play and the uncertainty premium contained in the mortgage spread. In a clear deviation from recent periods of stress, both the 10-year Treasury rate and the mortgage spread have risen, raising mortgage rates to levels not seen in nearly 15 years.

Ultimately, as the course of the economy and Fed activity become more certain, it is not clear whether Treasury rates will be higher or lower than they are now. But alleviating uncertainty should reduce the primary mortgage spread to normal levels, cushioning the potential effects of further Treasury rate increases. With a reduction in uncertainty, mortgage spreads could contract quickly, reflecting the limited supply of mortgage lending in a high-rate environment.

Higher mortgage rates, which are the result of higher Treasury rates, and wider mortgage spreads have pushed affordability out of reach for so many so quickly. If the mortgage spread were to decline to a more typical level, it wouldn’t totally reverse the effects of higher rates on affordability, but it would help more people pursue homebuying.

Let’s build a future where everyone, everywhere has the opportunity and power to thrive

Urban is more determined than ever to partner with changemakers to unlock opportunities that give people across the country a fair shot at reaching their fullest potential. Invest in Urban to power this type of work.