The reconciliation bill passed by the US House of Representatives in May would require adults to demonstrate they are working, volunteering, or participating in a work program for at least 80 hours per month or attending school at least half-time to qualify for coverage under the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. People who are pregnant, care for dependent children or individuals with disabilities, have certain health conditions, or have other specified characteristics would qualify for an exemption.

Supporters of the bill in Congress describe its goal as targeting so-called able-bodied adults who refuse to get a job. Proponents point to data showing that many Medicaid enrollees who do not qualify for the program based on disability either do not work or work inconsistently. They also say that millions of adults who are at risk of losing health insurance coverage because of the work requirement will lose their Medicaid only if they choose not to work.

Understanding why Medicaid enrollees aren’t working is essential for assessing the likely consequences of a work requirement. If enrollees can work but choose not to, the policy could theoretically provide incentives to join the labor force or increase their work hours. On the other hand, if enrollees face health problems and other barriers that prevent them from working, a work requirement could undermine their health and ability to work by taking away their health coverage while doing little to promote employment.

In a new analysis, we find that most Medicaid expansion enrollees who aren’t working or attending school have health conditions, caregiving responsibilities, and other barriers to work. Though on paper many of these adults would be exempt from the Medicaid work requirements proposed in the reconciliation bill, in practice, they would be at high risk of losing coverage.

Most Medicaid expansion enrollees work or attend school, and most of those who don’t experience barriers to employment

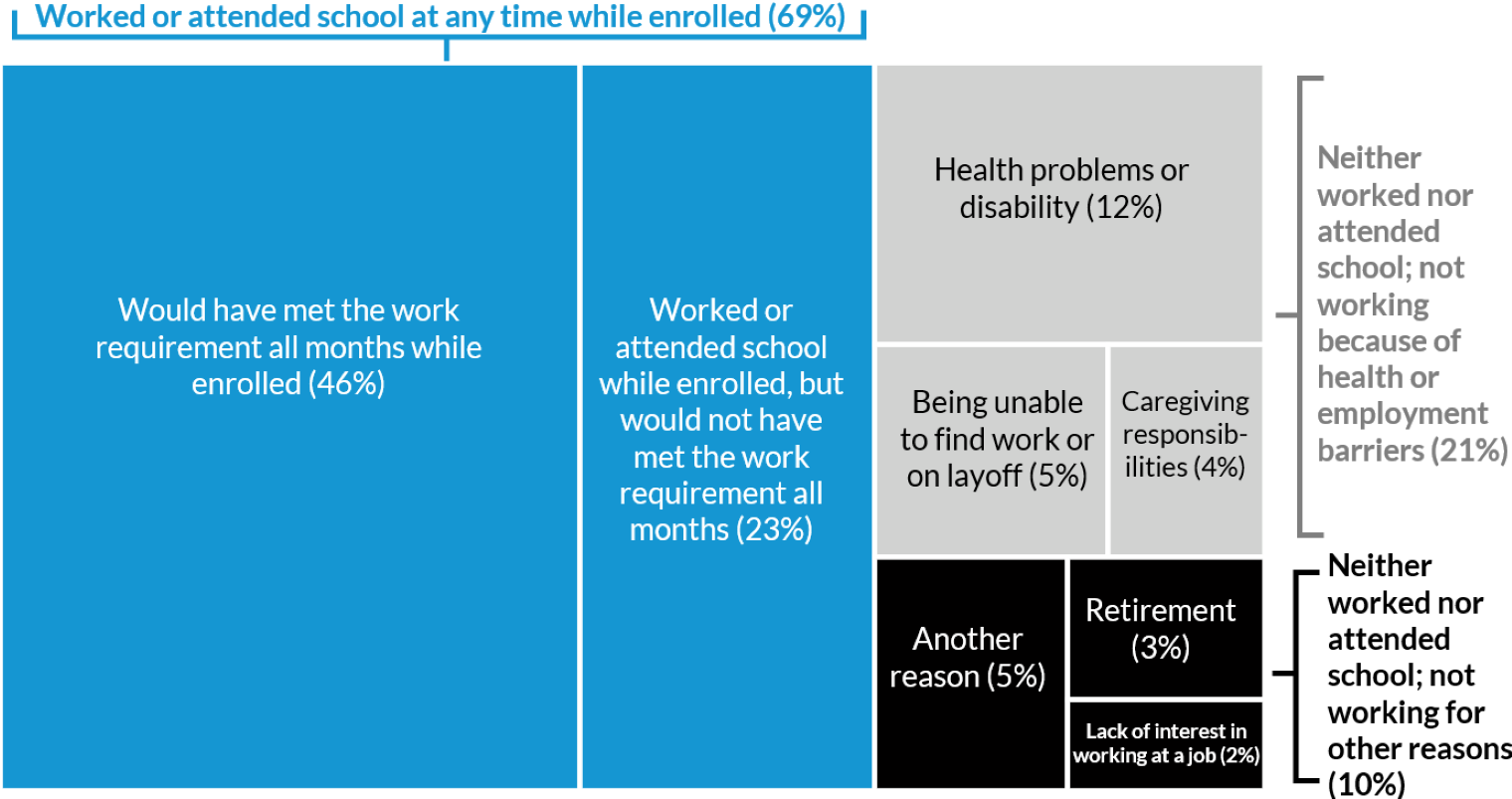

Studies have found most Medicaid enrollees already work. In a new analysis of data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation, we similarly find that 69 percent of Medicaid expansion enrollees not living with dependent children worked or attended school for at least part of the year while they were enrolled.

The remaining 31 percent neither worked nor attended school. Among this group, 12 percent reported they were not working because of health needs or a disability, and 5 percent said they were laid off or unable to find work.

Most Medicaid Enrollees Who Didn’t Work or Attend School Said Health Needs, Trouble Finding Work, or Caregiving Responsibilities Kept Them from Working

Medicaid expansion enrollees ages 19 to 64 without dependents

Source: Authors’ analysis of the 2018–20 Survey of Income and Program Participation.

Notes: Medicaid expansion enrollees without dependents include enrollees who lived in states adopting the Affordable Care Act

Medicaid expansion by 2017 and did not receive Supplemental Security Income, Social Security Disability Insurance, or Medicare

benefits. Meeting the proposed work requirement is defined as working at least 80 hours, attending school, or having earnings

equivalent to 80 or more hours multiplied by the federal minimum wage during the months a person is enrolled. Additional enrollees,

including those with health problems or disabilities or who have caregiving responsibilities, may qualify for exemptions from

proposed work requirements. Estimates reflect annual averages for 2017 to 2019.

A smaller percentage (4 percent) reported not working because of caregiving responsibilities, placing them among the millions of adults in the US providing care for an older adult, child, or disabled person within or outside their household. An additional 3 percent were retired, most of whom were ages 60 and older and a majority of whom were in fair or poor health or disabled.

Just 2 percent of Medicaid expansion enrollees without dependents report not working because they lack interest in having a job

House leadership has claimed that people who would become uninsured under Medicaid work requirements are currently taking advantage of the system because they refuse to work.

However, our analysis finds that among expansion enrollees without dependents, just 2 percent didn’t work or attend school and reported a lack of interest in having a job as their reason for not working. Based on our analyses of Congressional Budget Office projections, no more than 300,000 of the projected 15 million expansion enrollees without dependents subject to the work requirement wouldn’t be working because of lack of interest. This is consistent with findings from a recent study from the Brookings Institution.

Adults who are not working because they aren’t interested in having a job would therefore be only a small fraction of the 4.8 million (PDF) to 6 million adults projected to lose coverage because of new work requirements. This could also explain why previous Medicaid work requirement programs had no significant effect on employment even as they increased the number of uninsured adults.

Most Medicaid enrollees who don’t work or attend school have health needs or disabilities

Compared with Medicaid enrollees who work or attend school all or part of the year, Medicaid enrollees who don’t work are older, more likely to be female, and in worse health. Our analysis shows that from 2017 to 2019, nearly half (46 percent) of nonworking Medicaid expansion enrollees were ages 50 to 64, compared with 29 percent of workers and students.

Further, about two-thirds of nonworking expansion enrollees reported being in fair or poor health or having a functional limitation or a work-limiting disability.

They also used more health care on average than workers and students; more than half took daily prescription medications, and their rate of overnight hospital stays was twice as high.

More than half of nonworking enrollees were women, and nearly two-thirds lived with a child, a person with a disability, or an older adult, suggesting many may be providing unpaid caregiving. One in four experienced food insecurity.

Despite qualifying for exemptions, enrollees with health needs or caregiving responsibilities would be at risk of losing coverage under work requirements

Though the reconciliation bill makes exemptions for enrollees with certain health issues or caregiving responsibilities, millions of these individuals would still be at risk of losing Medicaid because of the added barrier of having to take action to claim an exemption.

When states implemented work requirements in the past, most enrollees who were able to maintain coverage had characteristics states could identify in available databases. In other words, states could automatically deem them compliant or exempt.

However, most of those who had to take action to maintain coverage—either by requesting an exemption or reporting their work activities to the state—experienced high rates of coverage loss. That’s despite the fact that most were engaged in the required activities or eligible for an exemption.

Though the reconciliation bill encourages states to automatically exempt enrollees where possible, it does not specify any automated processes states must use. That means many workers (and other groups, including parents) would still be at risk of coverage loss.

Further, nonworkers without dependents who should be exempted based on their health problems, disabilities, or caregiving roles would likely not be identified automatically because these characteristics are generally not captured in data sources readily available to states. Many nonworkers with work-limiting health problems could have to document their health conditions to qualify for an exemption and maintain their coverage. Such burdens could be even higher for people applying for Medicaid because obtaining proof of a health problem may require having access to the health care that Medicaid provides.

Even with a longer timeline for implementation than provided in the current bill, states would likely still struggle to develop the data-matching capabilities to provide automatic exemptions for all the health issues and other exemption criteria outlined in the bill because of the limitations of existing data sources. These challenges would be even greater on the current timeline, with work requirements mandated to begin at the end of 2026.

The bill includes $100 million to support state implementation, but this likely falls far short of what would be needed based on estimated implementation costs (PDF) from states that have tried to impose work requirements in the past and the sizes of funding requests in state-level work requirement proposals. Moreover, states wouldn’t face penalties for failing to provide Medicaid to people who qualify for an exemption or are fulfilling the community engagement requirements. However, they could be at risk of penalties if the federal government finds them to have provided coverage to enrollees who didn’t meet the work requirement.

Loss of coverage would worsen enrollees’ health and undermine their ability to work

Contrary to the image of Medicaid enrollees who don’t work as able-bodied young men choosing to play video games, nonworking enrollees are much more likely to be older adults, women, and people with health conditions, caregiving responsibilities, or other barriers to work. A Medicaid work requirement could further undermine their ability to work by taking away their health coverage. It would amplify their risk of serious adverse health consequences, including for people with mental health and substance use issues. It could also increase the uncompensated care burden on hospitals and health providers.

The reconciliation bill’s work requirements could save federal dollars, but it would be at the expense of the many adults with health needs and other employment barriers who rely on Medicaid coverage to pay for essential health care.

Let’s build a future where everyone, everywhere has the opportunity and power to thrive

Urban is more determined than ever to partner with changemakers to unlock opportunities that give people across the country a fair shot at reaching their fullest potential. Invest in Urban to power this type of work.