Americans are fed up with housing prices. A third say that housing costs prevent them from living near their jobs, and tens of millions of families in the United States are paying more than a third of their incomes for their dwelling costs. That’s the largest number of rent-burdened families in more than a decade.

President Biden’s 2025 budget seeks to address this issue through various policies, appropriately identifying that there is no single solution to the housing affordability crisis. Building more market-rate units is important, but evidence shows that greater access to public affordable housing subsidies, like housing choice vouchers, is also key to ensuring those with low incomes can secure safe and stable housing.

In a new analysis, I find that in high-housing-cost metropolitan areas, more housing construction is associated with higher housing affordability for the population, on average. Less restrictive land-use policies likely explain part of this outcome. The Houston region, for example, has less restrictive zoning policies, more housing construction, and higher overall affordability than the Boston region.

Yet, less restrictive zoning and high rates of housing construction alone are unlikely to meet the needs of the households with the lowest incomes. For those families, affordable housing is substantially more accessible in the Boston region than in the Houston region, in large part because of the greater availability of public subsidies for affordable units in Boston compared with Houston.

Building additional homes helps ensure housing affordability for middle-class families

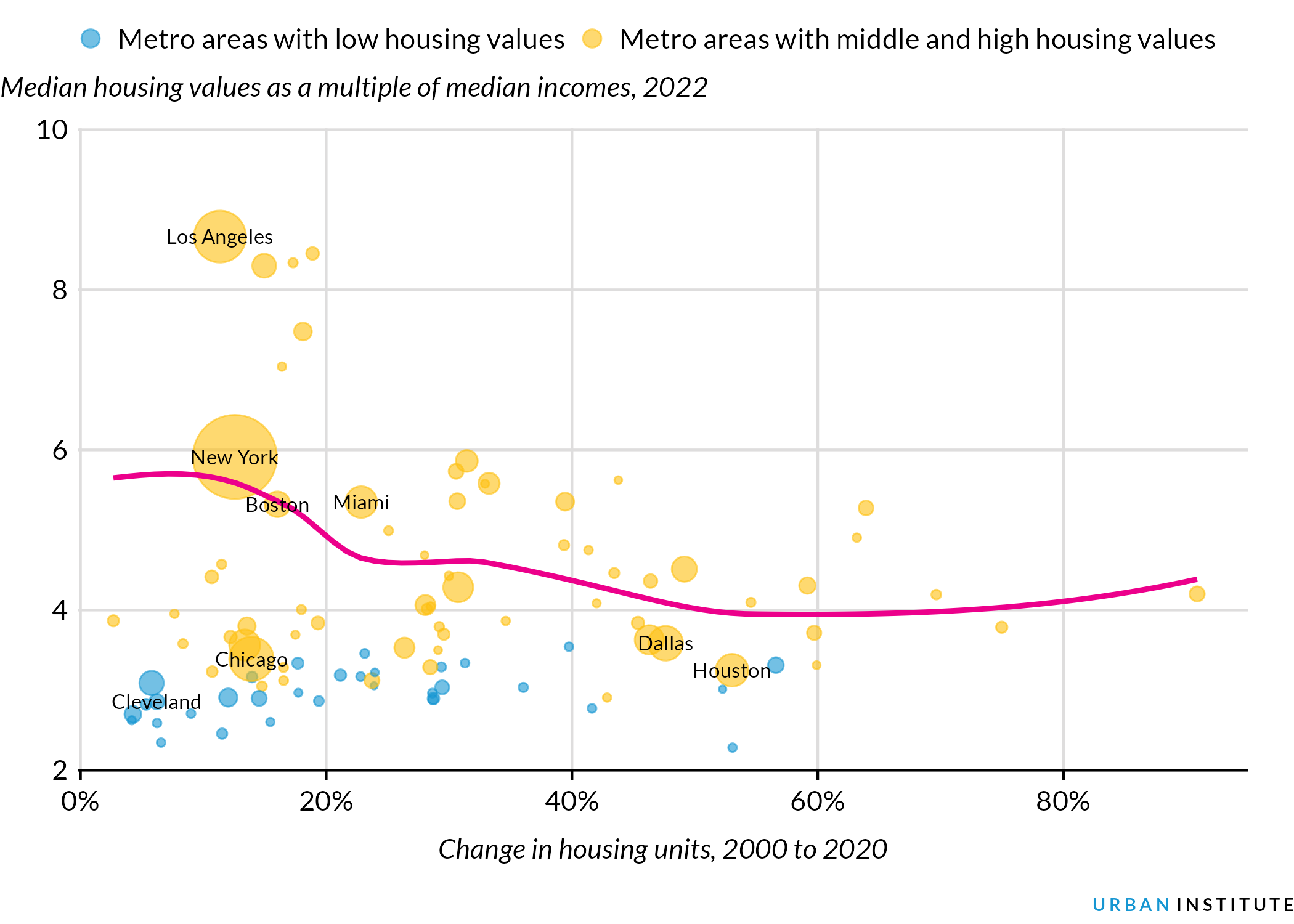

President Biden hopes to “build, build, build” more housing in the coming years, and there’s a good reason for that. Metropolitan areas that have greatly expanded their housing supply over the past two decades have substantially lower housing costs, on average, than areas with more limited housing supply increases.

For example, the Houston region’s housing stock grew by 53 percent between 2000 and 2020, with the median home valued at 3.2 times the median income. In the Boston region, however, the housing stock grew by only 16 percent—and the median home value is 5.3 times the median income. In other words, it is much easier for the typical middle-class family to afford a home in Houston.

In-Demand Metropolitan Areas with Limited Housing Production Struggle to Provide Homes Affordable to Middle-Income Households

Source: Author’s analysis of US Census Bureau decennial data (change in housing units) and 2018–22 American Community Survey five-year estimates (housing values and incomes).

Notes: Data show the 100 most-populous US metropolitan areas. The pink line shows the LOESS best-fit curve for metropolitan areas with middle and high housing values, defined as being in the top two-thirds of metropolitan areas, weighted by metropolitan area size. Points are scaled by metropolitan area size.

Local zoning policies explain only part of the housing affordability story

One explanation for this trend is that local zoning policies are limiting construction. Growing evidence has linked restrictive land-use regulations with less building and higher housing costs. Jared Bernstein, chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisors, said, “It’s really hard to make a difference…in this affordable housing space, without tackling land-use regulations.”

Recent research shows that the Boston area has substantially more restrictive land-use policies than the Houston region, which may explain why Boston has added less housing and has higher housing costs overall.

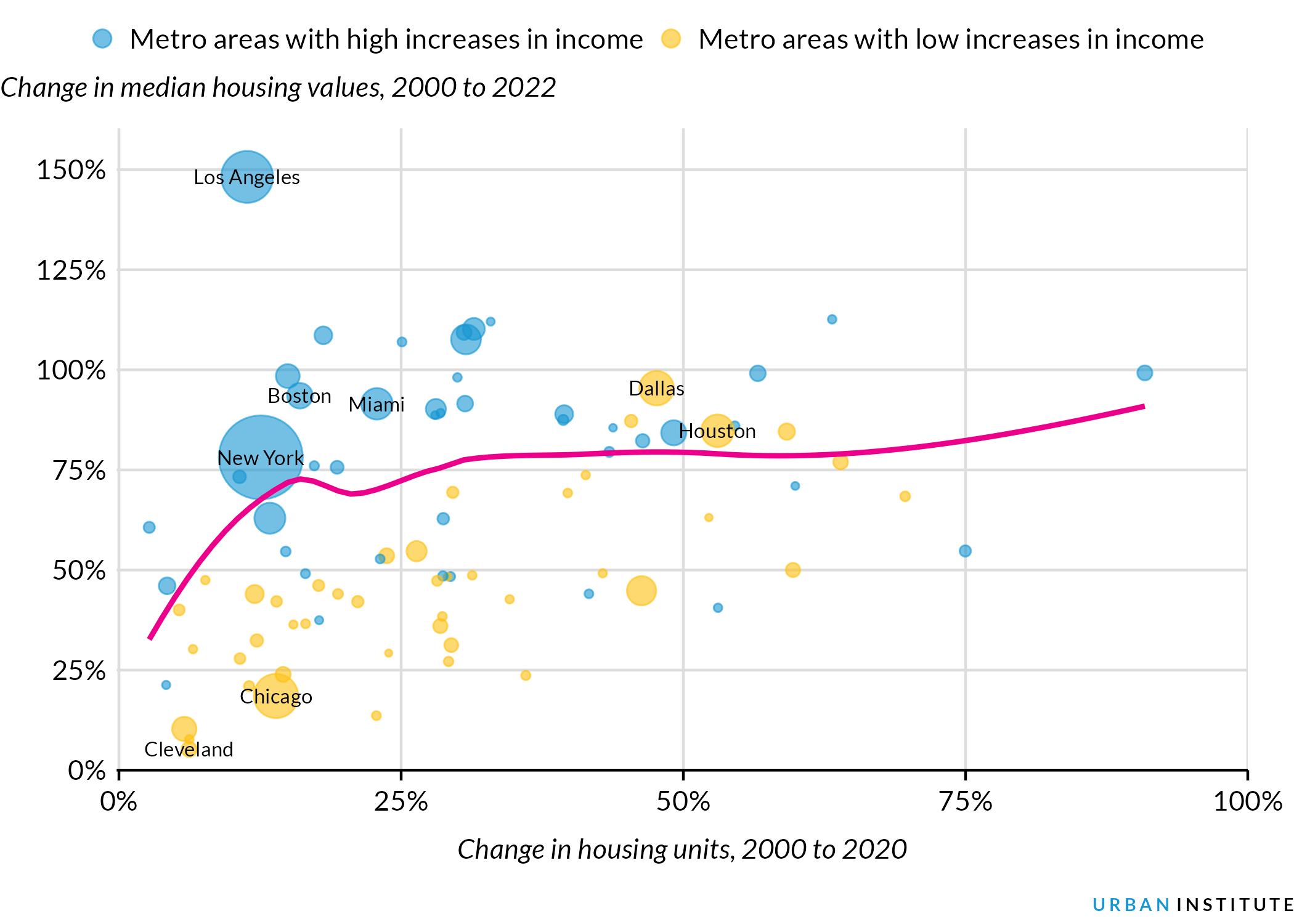

Even so, the devil is in the details, and zoning is only one part of the story. Housing costs across all large US metropolitan areas increased more quickly than incomes between 2000 and 2020. And regional differences in housing costs for the typical middle-class family are diminishing, despite varying levels of zoning restrictiveness and housing construction. During that period, for example, Houston’s median housing costs increased more than 6 times as quickly as median incomes there, while Boston’s housing costs increased 2.8 times as quickly.

Overall, Boston and Houston experienced similar rates of increase in median housing costs over the past two decades (94 versus 85 percent), even though Boston had much higher increases in median incomes (33 versus 14 percent) and much lower rates of housing construction.

Why is this happening? Lower-cost housing markets in regions like Houston attract newcomers, diluting the ability of new housing supply to reduce demand. Moreover, other issues affect affordability beyond new private-sector housing construction.

Houston’s Median Housing Costs Increased at a Similar Rate as Boston’s, Despite Houston’s Faster-Growing Housing Supply and Lower Increases in Income

Source: Author’s analysis of US Census Bureau decennial data (change in housing units, plus housing values and incomes for 2000) and 2018–22 American Community Survey five-year estimates (housing values and incomes). Incomes adjusted for inflation.

Notes: Data are for the 100 most-populous US metropolitan areas, with 12 areas not shown because of unavailable data. The pink line shows the LOESS best-fit curve for metropolitan areas, weighted by metropolitan area size. Points are scaled by metropolitan area size. Metropolitan areas with high increases in income had higher-than-national-median increases between 2000 and 2022.

Addressing housing affordability through private-market housing supply is inadequate

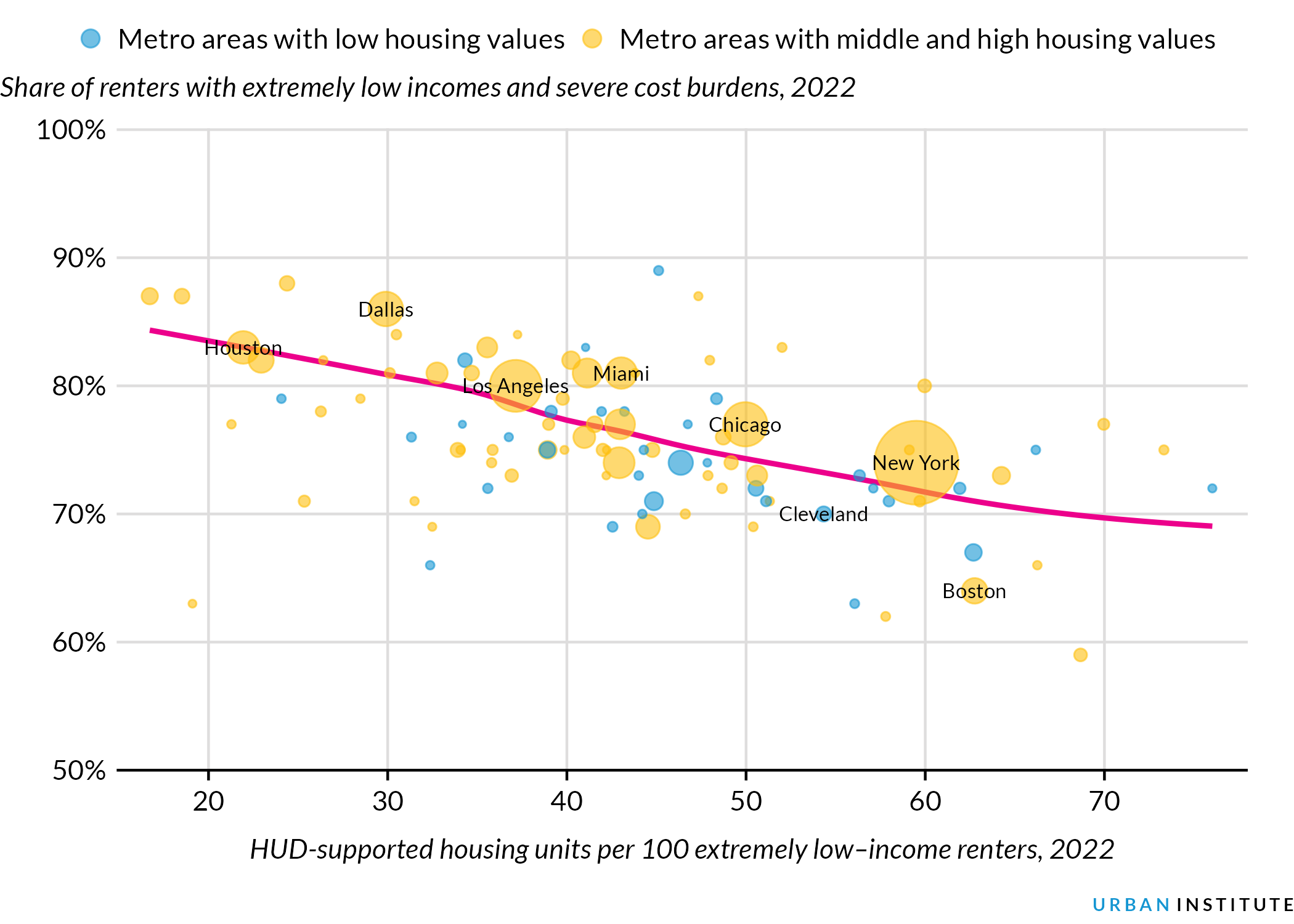

New construction alone can’t solve the housing affordability issue. Recent analysis from the National Low Income Housing Coalition shows a large gap in affordability for households with extremely low incomes (earning up to 30 percent of the area median income) across all metropolitan areas—regardless of zoning policies or housing supply increases. In the 100 most-populous metropolitan areas, these households are about one-quarter of all renters.

That gap is largely a product of inadequate public subsidies, such as support from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) through housing choice vouchers and public housing. These subsidies are important because developers generally cannot make money building or maintaining housing affordable for people with such low incomes.

On this front, the relative affordability of the Boston and Houston regions are reversed.

Houston has just 22 federally subsidized housing units for every 100 renters with extremely low incomes—and only 31 affordable units per 100 renters with extremely low incomes overall (meaning 9 of those affordable units are “naturally occurring” private-market units). Houston has even fewer affordable units when excluding those occupied by renters with higher incomes. Boston—despite its low housing production and tight zoning—has 63 federally subsidized units per 100 renters with extremely low incomes, equivalent to the overall number of housing units affordable to that group of renters. In other words, Boston is more affordable than Houston for households with extremely low incomes.

Similar trends play out across US metropolitan areas. Public assistance for affordable housing is a key tool to provide homes for the lowest-income households and is associated with fewer families spending more than 50 percent of their incomes on rent. Although 83 percent of renters with extremely low incomes in the Houston region do so, only 64 percent of those in the Boston region do. Boston is doing better, but even in the best-performing metropolitan areas, there is more work to be done to increase affordability.

Public Subsidies Play an Essential Role in Ensuring Housing Affordability for Families with Extremely Low Incomes

Source: Author’s analysis of 2018–22 American Community Survey five-year estimates (housing values), HUD subsidized unit data, and data produced by the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Notes: HUD = US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Renters with severe cost burdens pay more than 50 percent of income on rent. Data are for the 100 most-populous US metropolitan areas. HUD-supported housing units include project-based Section 8, housing choice vouchers, and public housing. Low-housing-value metropolitan areas have housing values that are in the bottom third nationwide. The pink line shows the LOESS best-fit curve, weighted by metropolitan area size. Points are scaled by metropolitan area size.

Policymakers should consider both more market-rate housing construction and more housing subsidies

These data illustrate the nuanced nature of the housing market in US metropolitan areas. Overall, homes are more affordable in regions where there has been more recent housing construction, indicating that additional supply is necessary to help meet America’s housing needs. Local, state, and federal policymakers seeking to improve affordability should consider reforming local land-use policies to encourage more building.

But public officials should also identify new means to expand housing subsidies. Overall, the federal government’s funding for units supported by HUD programs has declined over the past two decades, despite continuing need. Public supports can help fill the gap in housing affordability for renters with extremely low incomes. Both vouchers for residents to rent in private-market homes and subsidies for permanently affordable units are needed.

To truly tackle housing affordability issues in the US, policymakers from multiple levels of government should collaborate to link zoning reforms with increased housing subsidies for the lowest-income households. State governments, for example, could require localities to zone for a minimum level of new construction while providing added financial support for affordable housing.

Let’s build a future where everyone, everywhere has the opportunity and power to thrive

Urban is more determined than ever to partner with changemakers to unlock opportunities that give people across the country a fair shot at reaching their fullest potential. Invest in Urban to power this type of work.