The DC Housing Authority (DCHA) is under fire from the city council and advocates concerned about deteriorating conditions and what they view as the threat of privatization. The city council is considering two bills to address the problem that the

The vision for DC’s 11th Street Bridge Park is to connect some of the District’s lowest- and highest-income neighborhoods in a way that benefits everyone. But that’s a tricky value proposition. As developers and urban planners well know, when people of means embrace the neighborhoods they once ignored or avoided, the results can be devastating for those who already live there.

Bridge Park leaders know that risk, too, which is why a major goal of the project—apart from creating a lively arts-and-culture pedestrian span across the Anacostia River by 2023—is to achieve equitable development results in affordable housing, jobs, small business, and cultural preservation.

As we document in our recently released evaluation report on the first few years of their Equitable Development Plan’s implementation, Bridge Park and its partners are working to achieve this goal, and they appear to be succeeding so far.

Here are some of the quantifiable results collected over the past two years:

- 70 homes purchased by low- and moderate-income participants in the Bridge Park–sponsored Ward 8 homebuyers club

- 31 Bridge Park–sponsored construction trainees from Wards 6, 7, and 8 in full-time jobs

- 104 small businesses based in Wards 7 and 8 assisted by Bridge Park partner, the DC-based Washington Area Community Investment Fund, through loans and technical assistance

It may be appropriate to praise to Bridge Park leaders for their efforts to date, but it’s far too early to break out the champagne. Past, present, and future challenges must be addressed first.

First, the past. People seeking to equitably develop once-neglected neighborhoods must confront strong historical headwinds. As we discuss here and in an earlier report on the Bridge Park Equitable Development Plan, the circumstances of many of the people who live in DC’s most distressed neighborhoods arise from centuries of systemic oppression and discrimination, including zoning and development decisions that often favor those who are white, wealthy, and powerful.

Take Southeast DC’s Anacostia neighborhood, which sits at the eastern edge of the Bridge Park footprint, where a 19th century covenant once forbade “negroes, mulattoes, pigs, or soap boiling.” Even the seemingly well-meaning policies of the 20th century—like the construction of public housing—backfired, disproportionately sequestering low-income black residents into neighborhoods that white residents and others of more means turned their backs on for purposes of investment, habitation, or entertainment.

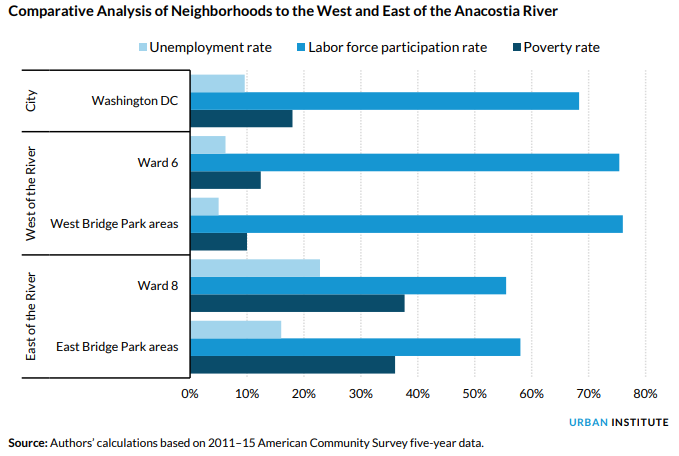

Now, the present. Numerous structural inequities and stark disparities thwart the prospects of many of today’s Ward 8 residents. The gaps in income, educational attainment, and employment prospects between residents on the Ward 8 and Ward 6 sides of the Bridge Park footprint often manifest as disproportionate rent burden and poor creditworthiness for the residents to the east, rendering the stolen assets of the past even less recoverable in the present.

And finally, the future. What will happen now that the attention of developers and high-income residents has refocused on Ward 8 as a desirable place to live and play? What should the expectations be for jobs and housing for residents with modest incomes, and how do these expectations account for factors like the disproportionately large population growth (PDF) (relative to the rest of the city) projected for neighborhoods like Anacostia, Congress Heights, and Fairlawn over the next 10 years?

We should not assume the answers to these questions are primarily in the invisible hands of the free market. The effects of Bridge Park or of any well-meaning entity—be it a city council, a bank, or an agency—should be viewed as pieces of a shared pie and assessed against common targets, such as jobs and housing, that all relevant parties, especially current residents, agree are fair.

Addressing the sins of the past, making progress in the present, and defining the hopes for the future are responsibilities Bridge Park and their immediate partners can’t and shouldn’t be accountable for on their own. Rather, it’s up to anyone who wants to live, play, lead, or make money in the neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River to do their fair share.

sponsors say would provide more oversight, promote transparency, and prevent privatization.

The first and most comprehensive bill would revoke the agency’s status as an independent municipal corporation and put it under direct mayoral control. The second would give the city council the power to appoint two additional members to the DCHA board and would require board members bring expertise in housing, financing, and resident services.

The DCHA’s leadership says it is open to a dialogue with the city council but vigorously deny that it plans to privatize the agency’s stock. In an open letter, the director said the agency is working on a creative plan that will preserve public housing and support residents. The DCHA is dealing with aging developments in need of major repairs and inadequate resources to address them.

The agency’s own audit estimates that a third of its units are at risk of becoming uninhabitable. And it acknowledges that too many residents are living with mold, peeling paint, lead dust, inadequate heat, and other conditions that threaten health and well-being.

DC is emblematic of larger systemic problems

The DCHA’s leadership (correctly) blames the state of its housing primarily on uneven federal funding for capital needs. This shortfall has forced the DCHA to forgo or postpone major improvements for its aging properties, some more than 60 years old.

Congress has increased allocations in the past two years, but the additional resources are not enough to address the backlog. The agency’s public statements also don’t acknowledge some of the other issues that have contributed to their current state: management inadequacies, weak US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) oversight, and a local government whose support for addressing the problems in the city’s public housing has waxed and waned over different administrations.

The DCHA’s situation mirrors the crisis affecting public housing across the country. The plight of the New York City Housing Authority, with its $34 billion backlog of maintenance needs and serious management deficiencies, has received the most media attention. The New York City mayor entered into a consent decree with HUD that calls for a special monitor, a new HUD-appointed executive director, and a plan to address the most urgent needs, but it provides no new funding for major repairs like new elevators, roofs, or electrical systems.

At the other end of the spectrum, in rural Cairo, Illinois, problems were so severe that HUD shuttered the public housing, and all the residents had to relocate to other cities. Other cities’ situations are not yet as extreme but still require urgent policy action from federal and local actors.

How the DCHA is planning to improve

The DCHA’s executive director released a statement listing steps it has already taken to address its challenges and inviting the city and other experts to help it create a plan to repair or rebuild its housing. The letter says the agency is applying for HUD authorization to “demo-dispo” (demolition and disposition) some of its most distressed properties, allowing it to demolish them and provide tenants vouchers.

The agency is also looking into expanding its use of the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program to obtain private funding to address more of its capital needs. Under RAD, public housing is “converted” into project-based Section 8, which allows housing authorities to leverage the property’s value to apply for private mortgages. Some RAD deals shift property ownership to private developers. Although the program has strong tenant protections, some advocates in DC and other cities view it as privatizing public housing.

Because of rising housing costs and rapid gentrification in DC, concerns about privatization and potentially losing public housing are high. The city’s long-delayed New Communities Initiative, which was to replace four developments with mixed-income housing, has been controversial, and tenants from one development have sued to stop relocation.

Advocates likely fear the agency’s stated plans to use RAD financing as part of its redevelopment strategy means privatizing—and losing—much of the housing available for DC’s lowest-income residents.

DC is overdue for a serious conversation about how to preserve its public housing. There are no simple solutions, and real progress will mean making choices that are sometimes unpopular. More management oversight or city control will not solve the fundamental problem that the housing authority’s capital needs far exceed the financial resources available. And regardless of the governance structure, public housing is important for the District, so residents and government stakeholders need to be involved in crafting solutions.

Let’s build a future where everyone, everywhere has the opportunity and power to thrive

Urban is more determined than ever to partner with changemakers to unlock opportunities that give people across the country a fair shot at reaching their fullest potential. Invest in Urban to power this type of work.