In 1975, Robert Martinson famously wrote that “nothing works” in treating convicted criminals and thus he concluded that rehabilitation in any form was not cost-effective. As discouraging as the criminal justice research was at the time, it was no more pessimistic than education, or public health, or child welfare research.

Today, however, we have mountains of evidence about effective programs. There is rigorous, transparent, objective evidence about what works in schools, what works to prevent violence, how we can help high-risk adolescents get on a better life path, and how to curb criminal offending in general. There are resources that can help guide governments find best practices in almost any sector, from child welfare to health care.

We don’t have a solution to every problem, but there are evidence-based solutions to many problems. But these programs focus on very narrow populations. If a government is looking to reduce drug use within the criminal justice system, we can provide precise estimates of the likelihood that community-based treatment will reduce new offending.

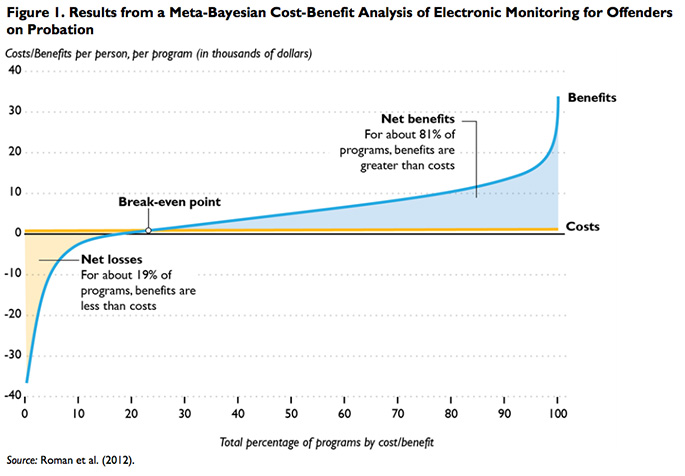

But what if government wants to reduce all types of criminal reoffending? Drug treatment alone is not enough to accomplish that objective. You also have to improve work skills, deal with mental illness, chronic homelessness, anger management, and more. There is no silver bullet for recidivism that can be summarized in a nice figure like the one above.

A few months ago, I was asked by a local government to help them think through what kind of social services they might finance through a new financing mechanism called social impact bonds (SIBs). SIBs are used to fund evidence-based programs, shifting the risk of new investment from the government to the private or philanthropic sector. The result could be an infusion of new money to fund programs demonstrated to work.

The local government’s particular question: How do we increase high school completion in our city by 20 percent?

Great question.

The problem is that what we do in the social sciences is ask very particular questions about the effectiveness of very narrow programs. If the goal is to reduce new offenses from highly at-risk youth, research provides an answer. If the goal is to increase high school completion among all youth, that is much more difficult to answer.

Florida Redirection is a cost-effective intervention for the highest-risk adolescents, a group that is a tiny (but expensive) fragment of high school dropouts. Reducing the high-risk adolescent dropout rate helps overall high school completion, but only somewhat. If you want to reduce overall high school dropout rates, you have to do lots of things. You have to have effective mentoring. You have to improve math literacy. You have to do out-of-the-the box things, like reduce asthma, which is a leading cause of truancy.

At the moment, we have no idea how to do these things in combination. Just like drug therapy for an illness, two really good medications could complement each other—or have adverse consequences. But that’s not how we study social service programs today.

In the United Kingdom, though, they are taking this issue head on. There, governments are testing 10 SIBs to improve the life chances of NEET youth (NEET being Not in Education, not Employed, not in a Training program), who often become huge drains on social resources as they age.

Each SIB tries a different combination of remedies for the NEET youth. And ultimately, that’s the way we will figure out the solution to these big policy problems.

The point is this: We don’t have solutions that cross programs and sectors yet. But we can if we use SIBs and other social innovations as a way to experiment, to test ideas about how evidence-based programs can work together.

Until then, research will have the wrong answers for policymakers’ questions, and policymakers will not pursue the evidence-based answers researchers can provide.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.