Nearly four years after President Lyndon Johnson declared the War on Poverty, Martin Luther King called on poor people to come together and demand their economic rights. The campaign was simple, he explained, ‘‘as pure as a man needing an income to support his family.” So why does financial independence still remain out of reach for so many men, even 45 years later, and what can be done to change that?

Today, over 15 million men between the ages of 18 and 44 cannot afford to support a family, according to a study we recently released with the Department of Health and Human Services. These men are disproportionately African American and Hispanic and over half made less than $10,000 in a year, below the poverty threshold for a single person. These men are in their prime years, when most men are building careers and forming families, but many of these men are not doing so.

According to ethnographers who have studied this population and service providers who have worked with them, most of these men want to support their families but lack the means to be a major breadwinner, in part because they lack the educational credentials to obtain high-wage jobs and in part because they are caught in the web of the criminal justice system that prevents them from reconnecting once they’ve fallen behind.

The low-income men who were the focus of our study lack a college education and live in families with incomes below twice the poverty line. More than half have never married and nearly one-third lack even a high school diploma. Only 61 percent were employed in 2008-10 and only 45 percent were employed full time for an entire year. Among low-income African American men, only 44 percent were employed during that period.

What’s more, incarceration rates have skyrocketed since King first announced his campaign in 1967. The lifetime chances of incarceration are nearly three times higher for a young African American man born in 2001 than in 1974 [figure 1]. Today, 932 out of every 100,000 men are incarcerated, but the rates are highest for African Americans, with 3,023 per 100,000 men in prison, compared with 478 for white men and 1,238 for Hispanic men.

So the policy question is—how can these men get on a career path that pays family-supporting wages and prevent the next generation from facing the same barriers?

Another door must open

Even after leaving the justice system behind, applicants with criminal records are largely ignored by potential employers, making jobs nearly impossible to attain. Without changes to public and private policies, these ex-offenders will continue to face high barriers to employment, leaving their families and communities to bear the consequences.

Healthier men, healthier families

Health problems can also hinder a person’s ability to work. Low-income men are more likely to report being in poor or fair health—and more likely to lack the health insurance needed to address it. The Affordable Care Act could make health care more accessible for some low-income men and improve their capacity for higher-earning jobs.

Regional differences matter

The scope of the ACA’s and other policies’ benefits, however, will depend on where low-income men live. Most live in large metropolitan areas and more than half in just 10 states—California, Texas, Florida, New York, Illinois, Georgia, North Carolina, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. While most low-income men reside in large cities, in smaller cities, the concentration is often higher. The demographics of the low-income men population also vary by region, with African Americans concentrated in the East and Southeast and Hispanics in the West. To truly support those who want to get on a better path, policies designed to lower barriers must address these geographic differences.

As we revisit the poverty question this year, let’s not forget that the question for many should be as simple as “can they earn an income that supports their family?” Right now, for about 15 million men, the answer is “probably not.”

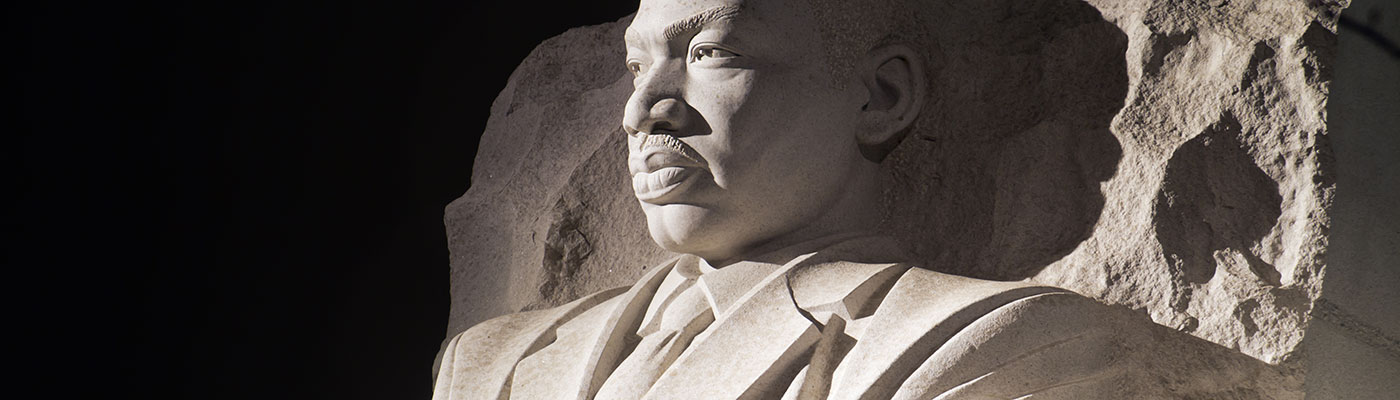

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial photo from Flickr user Scott Ableman (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.