On Monday, the White House and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released the long-anticipated final rule for the Clean Power Plan—the first federal attempt to directly regulate the greenhouse gases emitted from our country’s existing energy production sources.

What is the Clean Power Plan?

Basically, the plan calls for a national reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from existing electrical production plants by 32 percent from 2005 levels by 2030. It takes a state-by-state approach, setting individual targets based on most states’ emissions and allowing states multiple options for achieving them.

The plan’s three core “building blocks” include making plants more efficient, switching plant fuel from coal to natural gas, and moving toward renewable energy sources altogether. A fourth building block, end-user energy efficiency, was dropped (more on that later).

The press is focusing on the politics and partisan debates over the plan. Industry and advocates are combing through the details of the plan’s timelines and requirements, noting that much of the plan includes actions that are already underway. But, it’s worth paying special attention to how the plan affects low-income and marginalized communities.

What does the plan mean for working families?

Home finances: Partisan debates have especially focused on the cost to the general consumer, especially lower-income households who struggle to pay current energy bills. In this arena, unfortunately, the evidence base for most arguments is still a bit contested.

A US Chamber of Commerce-sponsored study suggests that the economy as a whole will be hit, resulting in increased end-user prices that would disproportionately cost middle-class and lower-income households to the tune of over $200 (based on assumptions made before the final rule).

In contrast, the White House and EPA project a savings of over $85 a year in utility bills by 2030 for the average American household, based on the plan’s expected changes.

Health: These financial outcomes don’t include other savings that might come as a result of the plan, especially projected health benefits from reduced pollutants—a special focus of the administration’s goals given that poor, African American, and Latino families live disproportionately near electrical power plants.

Jobs: Presuming that some of the working-class employees in industries supported by the status quo production (like coal mining) will need assistance, the plan asks states to tap into federal sources of workforce development and training funds, like the Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization Initiative.

Civic engagement: The plan requires states to proactively involve low‐income communities, communities of color, and tribal communities in the development of their compliance plans. The engagement is meant not just for transparency’s sake, but also to avoid future environmental justice concerns like the siting of the most egregious plants.

Housing and community conditions: A centerpiece of the final rule is the Clean Energy Incentive Program (CEIP), an optional pathway for compliance that rewards states that invest early in either the transition to renewable energy sources or in energy-efficiency programs for low-income communities.

The decision to drop the comprehensive energy efficiency “building block” is a hard pill to swallow, particularly for the nonprofits, local and state governments, and utilities that were looking to expand efficiency programs across the board. But its loss as a general strategy for the entire population and reincarnation as the CEIP may actually be more beneficial for low-income folks since, anecdotally, low-income households have benefited less from these programs that their wealthier counterparts.

Ultimately, everyone benefits from the long-term leveling off of greenhouse gas emissions by reducing exposure to the effects of climate change—effects that science agrees include increased extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and overall warming. The poor and marginalized communities in the United States, like those in the rest of the world, are the most vulnerable to these effects not only because of their increased physical exposure, but also because they lack the resources to mitigate, adapt, and defend against them.

When looking at all costs and benefits, then, the plan suggests savings for low-income families—potentially modest savings, but savings nonetheless. Combined with the White House’s announcement last month to expand solar installations for low-income households and myriad other federal efforts to date, the compliance plans and implementation actions that each state takes will ultimately decide the plan’s overall costs and benefits for working families.

What do we need to know to make better predictions?

While those plans are drafted, much more evidence needs to be built to determine how any group fares. Part of the challenge is that we don’t know really how—and how much—different groups consume, conserve, and or make decisions about energy, and what it takes to change consumption behaviors.

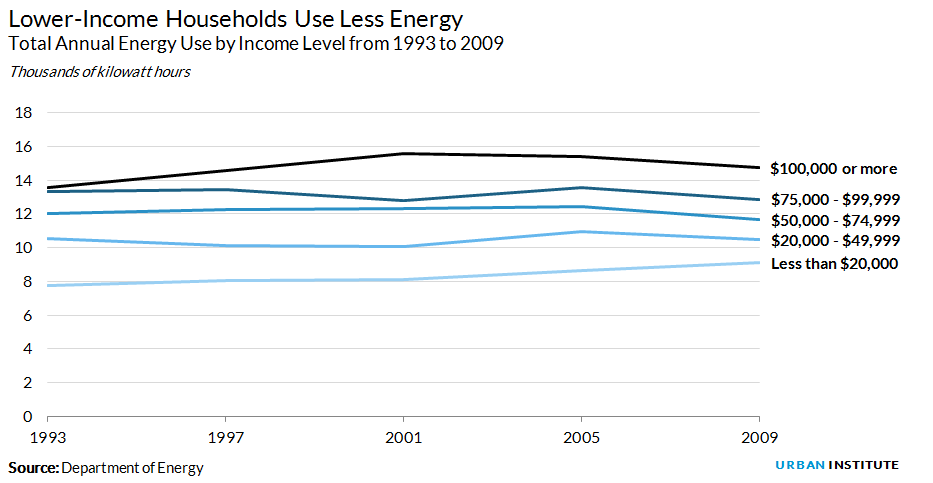

One study looking at the effect of energy regulation on low-income families suggests that the poor are more likely to live in regions that require more energy consumption, like hotter inland climes in California. Looking nationally, though, this specific claim is not generalizable. Department of Energy data suggest that poorer households historically use less energy and spend less on their energy bills. Poor households are also more likely to live in older, less energy-efficient homes.

What we do know is that these groups will be affected by both action and inaction. As President Obama said during the plan’s release: “If you care about low-income and minority communities, start caring about the air they breathe.” We also need to care about their bills, their homes, their jobs, and their life chances. So far, the plan does a reasonable job on these counts.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.