Serving limited-English-proficient (LEP) populations is a critical policy issue in a country where one in seven households is an immigrant household. As immigrants settle in a growing number of regions and communities, more and more local service providers and municipal governments must support diverse language needs. But how?

Some municipalities and counties are attempting to meet these needs by passing legislation or developing language access programs to formalize language access services. Washington, DC, passed its landmark Language Access Act in 2004, which required all government agencies with major public contact to assess the language needs of their clients, provide translation and interpretation services, and consistently report on and expand these services to respond to need. DC’s Office of Human Rights asked the Urban Institute to examine the first 10 years of implementation of the city’s language access policy and provide a demographic profile of the current LEP population.

Our report finds that District agencies have made strides toward providing language access services to the 1-in-20 DC residents who are LEP, despite challenges like resource constraints and a range of language needs.

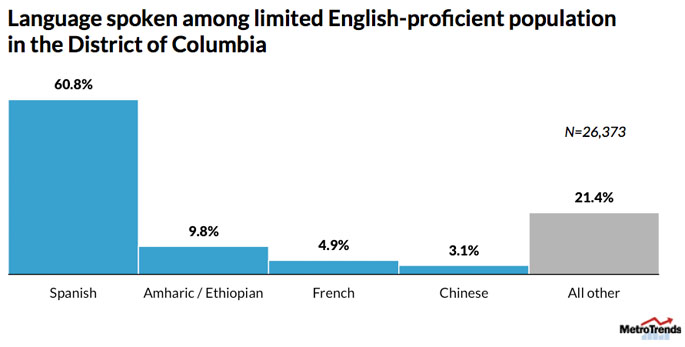

DC’s LEP population represents an enormous diversity of languages. While 61 percent speak Spanish and about 10 percent speak Amharic or another East African language, other languages spoken by LEP residents span from German, French, and Italian to Vietnamese, Chinese, and Tagalog to the West African languages Kru, Ibo, and Yoruba.

Rates of limited English proficiency vary widely by neighborhood. About 10.5 percent of Ward 4 residents are LEP, compared with 2 percent or less in Wards 7 and 8. But there is still a lot we don’t know about the LEP population, leaving some residents underserved and municipal agencies facing hurdles. How can agencies keep track of the language needs of their current clients? And how can they know the unmet language needs of difficult-to-reach populations? How can an agency know about potential clients’ language needs if those individuals are not approaching health providers to get treatment, are afraid to call the local police station, or don’t register their children for summer camp out of fear of being rejected, misunderstood, frustrated, or worse?

Rates of limited English proficiency vary widely by neighborhood. About 10.5 percent of Ward 4 residents are LEP, compared with 2 percent or less in Wards 7 and 8. But there is still a lot we don’t know about the LEP population, leaving some residents underserved and municipal agencies facing hurdles. How can agencies keep track of the language needs of their current clients? And how can they know the unmet language needs of difficult-to-reach populations? How can an agency know about potential clients’ language needs if those individuals are not approaching health providers to get treatment, are afraid to call the local police station, or don’t register their children for summer camp out of fear of being rejected, misunderstood, frustrated, or worse?

These are serious data problems, and solving them requires a multi-pronged information-gathering effort on the part of public-serving agencies about the language needs of their specific target group (children, the elderly, business owners, etc.). By itself, analysis of the best demographic data is not sufficient to assess the nuances of local needs.

It is critical that agencies combine demographic data with careful tracking of their client population’s language needs and how they evolve over time. Reaching out to local experts and stakeholders about who in the community is not currently accessing available services is another crucial step. To provide meaningful access to city services for all DC residents, strategic use of scarce translation and interpretation resources must be informed by evidence about the needs of the community as the population of DC continues to grow and evolve.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.