A version of this post originally appeared on RealClearPolicy.com

African Americans share a uniquely high exposure to poverty in the US. Through a century of various explicit public and private housing discrimination practices, African Americans of all socioeconomic classes live in higher poverty neighborhoods than whites of similar income. Living in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty is a phenomenon relatively common to African Americans, but almost unknown among white populations.

Exposure to concentrated neighborhood poverty harms kids’ life chances. But it’s not just African American kids’ neighborhoods that expose them to concentrated poverty. Black kids are also uniquely exposed to concentrated poverty in their public schools.

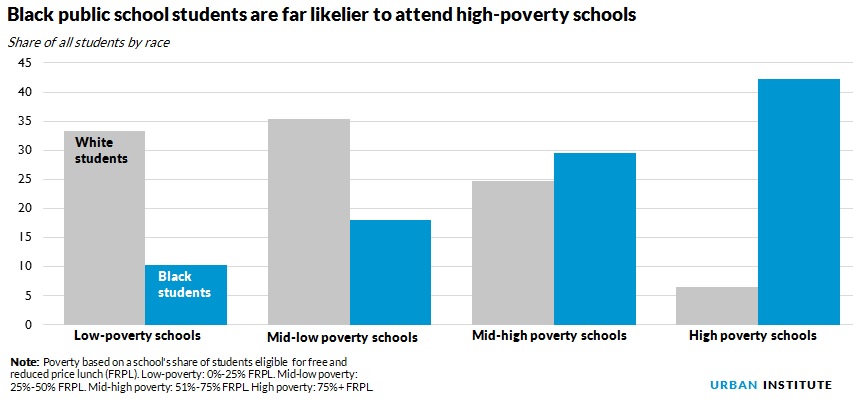

Black students are more likely to attend high-poverty public schools

According to 2011-12 school year data from the US Department of Education, about 33 percent of all white students attend a low-poverty school and a mere six percent attend a high-poverty school. In other words, white kids are about five times more likely to attend a low-poverty school than a high-poverty school.

It is precisely the opposite pattern for African American kids, for whom attending a high-poverty school is commonplace. Over 40 percent of black students (about 3.2 million) attend a high-poverty school and only about 10 percent attend a low-poverty school.

Segregation by poverty, segregation by race

This “poverty segregation” in public schools tends to go hand-in-hand with racial segregation. Many African American students attend highly racially segregated schools, and when they do, they are more likely to end up in high-poverty schools, too.

When African American students attend a segregated school where the majority of students are kids of color, over half are attending high-poverty schools (53 percent), compared with 42 percent of all black students. As racial segregation in schools increases, so does the concentration of poverty. About 65 percent of black students in a school with a population that is three-quarters or more students of color are attending a high-poverty school.

At the extreme end of school segregation are schools with almost no white students (at least 9 out of 10 kids are students of color). Among black students attending these schools, 73 percent are in a high-poverty school, and remarkably few (five percent) attend a low-poverty school.

What’s more, it’s not a small number of black children attending such poor and racially isolated schools: over 2.1 million black students (or about 28 percent of all black students) attend schools that are both high-poverty and 90 percent students of color.

Schools can’t address segregation and poverty on their own

The effects of exposure to concentrated poverty are large and long-lived and should be of concern to all institutions and systems responsible for the livelihood of black children. But it is not the responsibility of our school system to reduce poverty.

Poor, segregated schools are a symptom of a broader array of racial equity issues that flow from neighborhood segregation and housing discrimination, legal barriers to school desegregation, and inequitable policies that precluded African American upward economic mobility in the past 40 years and precipitated recent significant downward mobility, with many falling out of the middle class.

Addressing how such class immobility and neighborhood stagnation manifest in poor, segregated schools requires comprehensive housing and school policy solutions so that black children are not inheriting concentrated disadvantage from one generation to another.

Housing programs can alleviate the concentration of race and poverty in schools. Promising initiatives include mobility programs with information for parents on neighborhood and school quality, rigorous enforcement of fair housing policies, and assistance with locating affordable housing in low-poverty neighborhoods with high-quality schools.

Regional school policy can also recognize that poor, racially isolated schools and neighborhoods are damaging to regions as a whole because the health of cities and their suburbs are intimately linked, then redraw school district lines (which often reinforce inequality) to cross suburb and city lines or incentivize resource-rich suburban schools to accept low-income transfers.

These are not untested, abstract ideas or fiscally burdensome initiatives, but proven policy and programs that can reduce concentration of race and poverty in our schools and neighborhoods. The best solutions leverage existing policies and funding to promote sustained racial and socioeconomic diversity. But the neighborhood school cannot solve these problems alone. No school should be expected to systematically outperform its neighborhood and overcome generations of compounded disadvantage.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.