Yesterday’s CBO report predicts that the Affordable Care Act will cause many workers to reduce their hours or quit working altogether. Is that true? If so, what does it mean?

These Urban Institute experts offer their thoughts.

Four in 10 say health insurance concerns affected critical labor market decisions prior to the implementation of the new Marketplaces and other ACA coverage provisions.

Lisa Clemans-Cope, Steve Zuckerman, and Michael Karpman are all health policy experts with the Urban Institute's Health Policy Center

CBO reports that most of its estimated employment effects due to the ACA will come from allowing individuals to choose to work fewer hours, to start new businesses or not to work at all. To understand the tradeoffs individuals had been forced to make prior to full implementation of the ACA, the December 2013 Health Reform Monitoring Survey (HRMS) asked respondents whether health insurance concerns affected their employment, education and retirement decisions in the past 12 months.

We found that 37.7 percent of nonelderly adults (age 18–64) had concerns about health insurance coverage in the past 12 months that affected decisions to start a business, change jobs, work fewer hours, retire, or go back to school (see figure below). Changing jobs was the most common decision affected by insurance coverage concerns, cited by 14.5 percent of respondents. (More detailed analyses of these data, including methodology of the response categories, will be available in the next few weeks.)

These findings show that prior to ACA implementation, maintaining access to insurance coverage had been shaping family and individual decisions. The ACA makes it possible for people to make these key work, education, and retirement choices without worrying about being able to get coverage.

Newer evidence is not always better evidence

Austin Nichols is a senior research associate specializing in labor economics, public finance, and applied econometrics.

The Affordable Care Act is not projected to cost the economy 2 million jobs over the next 10 years as many have claimed today. Rather, CBO predicts a 1 to 2 percentage point drop in total hours worked (some people not working, others working less), which is a labor supply shift, not a labor demand shift. When labor supply declines, we expect wages to rise, but when labor demand declines, we expect wages to fall, so these shifts are not the same thing at all. But—now that we’ve got that straight—that drop in hours worked is overstated. The evidence actually suggests that the ACA will have no impact on employment, because neither labor supply nor labor demand will shift much.

In its report, the CBO looks at a few policies assumed to affect labor supply: new exchange subsidies, some new taxes for higher-income folks, and Medicaid expansions mostly for nondisabled, childless adults and higher-income families. CBO assumes that each of those policies depress aggregate labor supply (on net) by discouraging work, but, in fact, they may have no net effect or even a positive effect on labor supply (there are many labor market effects to add together, and much uncertainty about the relative sizes of those effects).

Exchange subsidies affect people too well-off for Medicaid but not firmly middle class (under 4 times the poverty line) who do not have an affordable employer-sponsored health plan. CBO predicts the phase-out of the subsidies will operate like a tax and push people to work less. But the 2006 Massachusetts reform had negligible impacts on labor supply. Zero would be an equally good guess as to the likely net effect, instead of CBO’s larger estimate, but something in between seems reasonable.

On the effect of Medicaid expansions, CBO cites four papers on page 121 (what, you didn’t read the footnotes in appendix C?). The first, a summary of all research up to 2002, concluded that “health insurance is not a major determinant of the labor supply … of low income mothers.” The second, a highly regarded experimental study providing the best evidence to date, found no significant impact on employment.

The next two papers cited found that Medicaid had significant impacts on employment, but neither paper has the unbiased evidence of the experimental study. Let’s take a closer look at one of those two studies. The paper evaluating Tennessee’s 2005 move to remove childless adults from the state’s Medicaid program purportedly “shows a rise in employment rates with the withdrawal of Medicaid coverage from childless adults who had previously been turned down for private insurance.” In other words, when you take free health insurance away from childless adults, they are more likely to work. If you assume giving people health insurance and taking it away has a similar impact, Medicaid expansions cause decreased labor supply.

But the evidence from Tennessee is mixed at best. The paper compares the change in employment in Tennessee with the change in employment in other Southern states that did not change their Medicaid policies for childless adults. (The authors did this to account for other labor market shifts common to Southern states.) When I tried to replicate the paper’s findings a few months ago, I found no significant effect of the policy change on employment. Further, findings vary considerably based on what other factors are taken into account. The measured change in employment in many models is actually positive, though still a statistical zero. The best guess is that Medicaid expansions have no effect on labor supply.

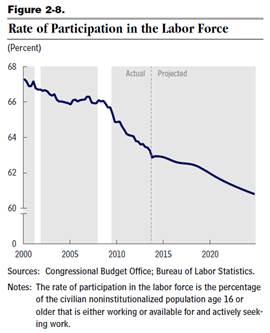

However, even if the ACA has no impact, the labor supply will still steadily decline in the coming years. As the population ages, more people will stop working or will work less. We will never again reach the peak labor force participation rates of 1999, when the Boomers hit their stride.

CBO estimates of employment effects counter to findings from Massachusetts’ reform

Lisa Dubay and Sharon Long are health policy experts with the Urban Institute's Health Policy Center

Yesterday’s CBO report renewed the heated debate about whether the ACA will be a “job killer” or a key to ending the “job lock” that traps many workers in undesirable jobs to retain their employer-provided health insurance. ACA requirements for large employers to provide coverage could raise compensation costs, thus reducing the number of employees. Employees, however, may view the availability of Marketplace subsidies as an opportunity to change jobs, start a business, go back to school, or even retire.

Only time will tell what the actual effects will be, however, evidence from Massachusetts’ comprehensive health reform effort suggests minimal effects on employment. 2012 research showed that, immediately following the state’s 2006 health reform law, employment trends closely mirrored states with similar employment patterns to Massachusetts preceding its reform.

Employment trends weren’t the only similarity in Massachusetts and comparison states following health reform implementation. Job trends also echoed comparable states, even among the firms, industries, and worker types most likely to be negatively affected if health reform had stifled economic growth, such as lower-skilled or younger workers or those in the retail, food, or hospitality service industries.

We also found that the Massachusetts reform did not slow economic growth. Massachusetts’ GDP continued to grow under health reform and actually increased relative to the rest of the country. Between 2006 and 2008, Massachusetts GDP grew by 2.4 percent while rest of the nation’s grew by only 1.1 percent. While there are many reasons the economy could have grown more steadily in Massachusetts, it seems clear that economic growth was not stunted by health reform.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.