The quality of public-service delivery in developing countries depends on accountability for public-sector employees, but what does it take to make accountability the norm rather than the exception?

According to the 2004 World Development Report, the long route of improving service delivery involves accountability through political mechanisms like the electoral system and politicians’ oversight. But the short route—accountability through the direct relationships between service providers, clients, and the local community—can often be just as effective.

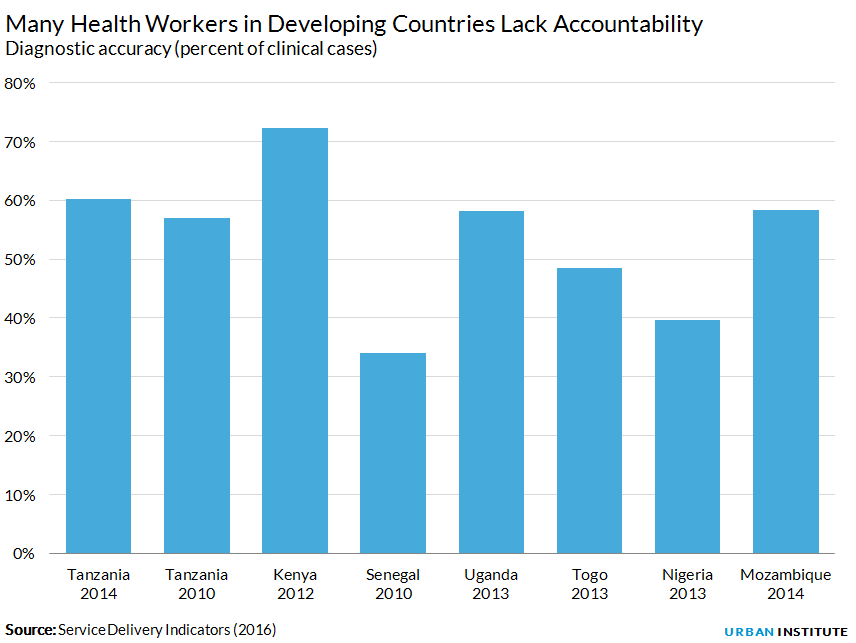

Social service delivery is still weak in many developing countries, particularly those in Africa, but increasing accountability could make a difference.

In Tanzania, a lack of accountability in the public-health and education sectors has serious repercussions for local communities through important social indicators, despite some incremental gains:

- In the health sector, 33 percent of doctors are absent from facilities. Health providers can correctly diagnose only 60 percent of five common conditions, and only 5 percent of nurses can correctly diagnose more than four cases. Half of facilities lack electricity, clean water, and improved sanitation. There are persistent rates of drug shortages (40 percent) and inadequate vaccine storage facilities in 75 percent of cases.

- In education, 47 percent of teachers in Tanzania are absent from classrooms, reducing the teaching time to approximately three hours instead of the scheduled six hours. Teachers often lack sufficient academic and pedagogical skills to teach; equipment and textbooks are in short supply; and the pupil-teacher ratio remains high at an average of 43 pupils per teacher.

Is there a way forward through social accountability?

The 1978 National Education Act of Tanzania set up the structure of the country’s education sector and included guidelines for the interaction between schools and the local communities. It created a convoluted chain of relationships that made it difficult to understand who reports to whom, even for a seasoned legislator.

In reality, schools and communities barely interact. The reporting structure is confusing, and many community members feel that because the elected school representatives were chosen by the community, representatives will make the best decisions. But when a community does not hold its elected representatives accountable for decisions, those decisions start to benefit the community less and the elected representatives more.

In the health sector, only 10 percent of the health facilities had client feedback systems in 2014 and 2015, a 6 percent increase in the last 10 years. But when 90 percent of health facilities still have no way for the community and patients to provide feedback, it is difficult for facilities to improve.

In addition, 85 percent of the facilities have no quality-assurance system. Without a system to monitor the inner workings of the health facilities, health workers have no reason to worry about being held accountable for the quality of their work, or even showing up.

Giving citizens power will help overcome the cycle of poor employee performance

Up-to-date, relevant, and credible information from providers and public authorities can help citizens better understand their rights, service standards, budgets and financing, and service organization. A perceived lack of demand for this information should not be an excuse to withhold it or discourage citizens’ engagement.

But what prevents citizens from seeking information?

We cannot assume that when provided information, citizens will be willing to transform information into action and pressure policymakers and providers to better serve them. Particularly in poor and rural areas, citizens either have other priorities or do not see any value in participating or knowing the public affairs. They may have low expectations or feel that they have no power over the decisionmaking process. (This is called “rational ignorance.”) Poverty and low education levels exacerbate the prevailing information gap between providers and clients, leading to a vicious cycle of lack of accountablity, poor performance, and distrust.

Culture can impede greater engagement and action

In Tanzania, a culture of fear makes citizens reluctant to challenge authority, teachers, and health providers. Also, responding to citizens’ needs requires policymakers and providers to change behaviors, ethics, responsibilities, and incentives, which can take time. Accountability frameworks that give a voice to users and improve service delivery promote greater engagement and participation.

The short route is scenic and winding, after all

Providing timely and relevant information to users, designing accountability frameworks that promote citizen engagement and take culture into account, and evaluating accountability will lead to better service delivery. But this type of social accountability faces challenges that may take more time to address. If accountability works, citizens can influence political and administrative institutions, which will increase quality of service as providers’ effort and ability improves. This continuous improvement will foster public trust in public-service delivery and weave a stronger social contract.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.