We're grateful to our smart and thoughtful readers for pointing out our errors in assembling these data. We've posted amended text, charts, and conclusions immediately below. The original post appears at the bottom for those who wish to compare the changes. Our apologies.

Despite the damage wrought by the mortgage crisis of 2008 and the ensuing Great Recession, the general narrative has been that an increasing number of young, educated, and (largely) white people are moving back into urban neighborhoods, bringing their tastes, lifestyles, and salaries along with them. Cities as diverse as Los Angeles, DC, Houston, Atlanta, Seattle, and Detroit are in the process of building or planning new rail transport, while formerly blighted urban neighborhoods are seeing new investment, rising property values, and increasing numbers of white, educated residents.

Respectively called revitalization or gentrification, this trend is fraught with contention between those who applaud these changes, and those who see them as harmful to the older residents of the affected neighborhoods.

But is this narrative driven by a handful of hipsters in Brooklyn and San Francisco or by urban revitalization trends in multiple places?

To figure that out, we examined a few indicators of demographic change for a group of 10 mid- to large-sized cities in 2000 and 2012. We selected the cities based on their reputations for being vital or attractive places and for their geographic diversity. A few—Austin for example—has drawn job seekers through a strong economy and thriving cultural scene. Pittsburgh, on the other hand, is often seen as a strong example of economic revitalization in the rust belt. While they do not represent the country as a whole, these cities do provide a starting point for a discussion.

What we found was that, despite the popularity of the revitalization narrative, the city-level indicators presented here provide mixed evidence that gentrification on the neighborhood level is affecting demographics in these cities overall.

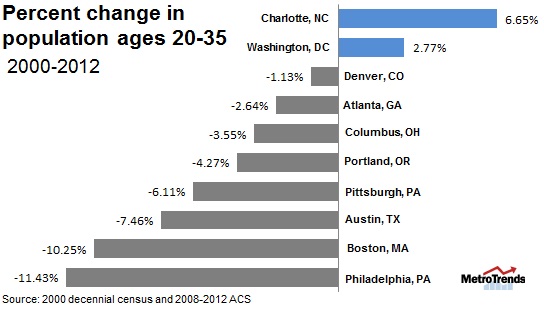

The number of people in the “hipster” or “young professional” age group of 20 to 35 has increased in all 10 selected cities, although not as much as we may be inclined to believe. Charlotte and Washington, D.C. have seen the highest levels of growth, with increases of 27.5% and 20.3% respectively in the 20-35 cohort.

Both of these cities have relatively resilient economies based on large government, academic, and commercial employers. However, other economic draw locations such as Atlanta and Denver have seen increases by relatively modest 5.4% and 7.8% respectively.

The college-educated population in cities is going up

Are more families with children living in cities?

However, this indicator on its own does not point to educated families choosing the city. In their recent article, William Sander and William A. Testa found that, despite a relatively high number of parents with school-aged kids living in the central cities, college-educated parents overwhelmingly choose the suburbs.

Gentrification isn’t the only trend shaping cities

We know that revitalization is happening in the neighborhoods of many American cities. But what the numbers here tell us is that gentrification is not the only change these cities are seeing, and in many cases, may not be the dominant trend, even in healthy cities.

In any case, population increases, decreases, and compositional changes are likely to have important implications for neighborhood amenities and community institutions. It may be that increases in college-educated residents result in increasing demands for better or different educational opportunities for children in central cities or that quality schools encourage college-educated residents to settle down in central cities. _____________________________________________________________________________________

Thanks to the sharp eye of one of our readers, we've become aware of a technical error in our calculations for this post. We are updating the numbers now, and some of the conclusions will change. An updated version of this post appears above.

Despite the damage wrought by the mortgage crisis of 2008 and the ensuing Great Recession, the general narrative has been that an increasing number of young, educated, and (largely) white people are moving back into urban neighborhoods, bringing their tastes, lifestyles, and salaries along with them. Cities as diverse as Los Angeles, DC, Houston, Atlanta, Seattle, and Detroit are in the process of building or planning new rail transport, while formerly blighted urban neighborhoods are seeing new investment, rising property values, and increasing numbers of white, educated residents.

This trend, whether it’s known as revitalization or gentrification, is fraught with contention between those who applaud these changes, and those who see them as harmful to the older residents of the affected neighborhoods.

But is this narrative driven by a handful of hipsters in Brooklyn and San Francisco or by urban revitalization trends in multiple places?

To figure that out, we examined a few indicators of demographic change for a group of 10 mid- to large-sized cities in 2000 and 2012. We selected the cities based on their reputations for being vital or attractive places and for their geographic diversity. A few—Austin for example—has drawn job seekers through a strong economy and thriving cultural scene. Pittsburgh, on the other hand, is often seen as a strong example of economic revitalization in the rust belt. While they do not represent the country as a whole, these cities do provide a starting point for a discussion.

What we found was that, despite the popularity of the revitalization narrative, the city-level indicators presented here provide little evidence that gentrification on the neighborhood level is affecting demographics in these cities overall.

More young adults are moving out than moving in

Cities that have seen growth in this cohort—Washington, DC, and Charlotte—both have relatively resilient economies based on large government, academic, and commercial employers. However, the population of young professionals in Austin, another economic draw location, has declined.

The college-educated population in cities is going up

Are more families with children living in cities?

Key to the discussion of neighborhood change and sustainability is the number of families with children choosing to live in central cities. While table 3 does show a decline in the number of families with children in half the selected cities, the other half shows growth, including a remarkable 21.5 percent increase in Austin and 38.3 percent in Charlotte.

However, this indicator on its own does not point to educated families choosing the city. In their recent article, William Sander and William A. Testa found that, despite a relatively high number of parents with school-aged kids living in the central cities, college-educated parents overwhelmingly choose the suburbs.

Gentrification isn’t the only trend shaping cities

We know that revitalization is happening in the neighborhoods of many American cities. But what the numbers here tell us is that gentrification is not the only change these cities are seeing, and in many cases, may not be the dominant trend, even in healthy cities.

In any case, population increases, decreases, and compositional changes are likely to have important implications for neighborhood amenities and community institutions. It may be that increases in college-educated residents result in increasing demands for better or different educational opportunities for children in central cities or that quality schools encourage college-educated residents to settle down in central cities.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.