State governments often use their tax system to partner with the private sector on economic development initiatives. A key part of their economic development strategy, states use tax incentives as one tool of economic development to compete with other states and globally for investment, jobs, and income. This brief is part of a State and Local Finance Initiative project on state economic development strategies.

Full Publication

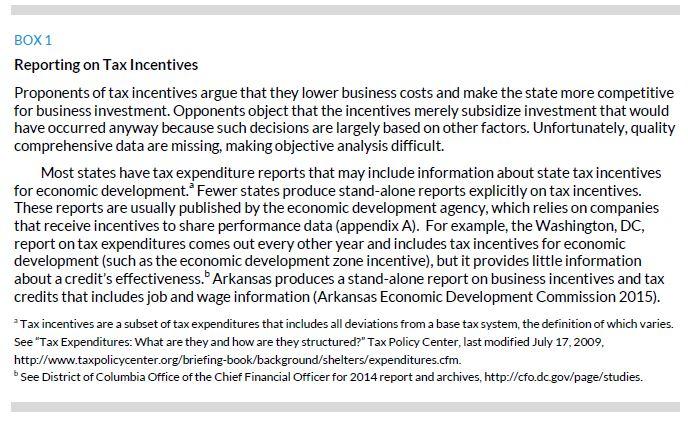

State governments often use the tax system to partner with the private sector on economic development initiatives. In particular, tax incentives are a key part of many states’ economic development strategies. They are used to achieve goals beyond economic growth or job creation, such as spreading economic activity throughout the state (through geographic targeting) and focusing on perceived high-value industries. States also use tax incentives to compete with other states and foreign countries for business investments that promise jobs and increased economic activity. Proponents argue that tax incentives are necessary to attract businesses and that the costs of those incentives are partially or wholly offset by the additional tax revenue derived from the increased economic activity. Opponents maintain that tax incentives are an inefficient allocation of resources, spending scarce state tax dollars on actions that would have been taken without the tax breaks. This controversy has led many states to require more comprehensive reporting and evaluation and for the Government Accounting Standards Board to establish new rules for government financial statements that require reporting on tax abatements, a particular form of tax incentives (Francis 2015; Pew Charitable Trusts 2015).

Taxes are a consideration in business decisions about location, but they are not the only one. Although firms welcome tax incentives, availability of transportation and low labor costs more often drive business decisions about expansion or relocation. Corporate site selection professionals rank the availability of skilled labor and adequate land and infrastructure higher than they rank tax policy.1 A comprehensive review of North Carolina incentives, for example, found that companies ranked incentives below skilled labor availability, highway access, general tax rates, and the regulatory climate (Lane and Jolley 2009). But of the direct actions available to state governments, tax incentives were ranked higher than training programs or financial assistance.

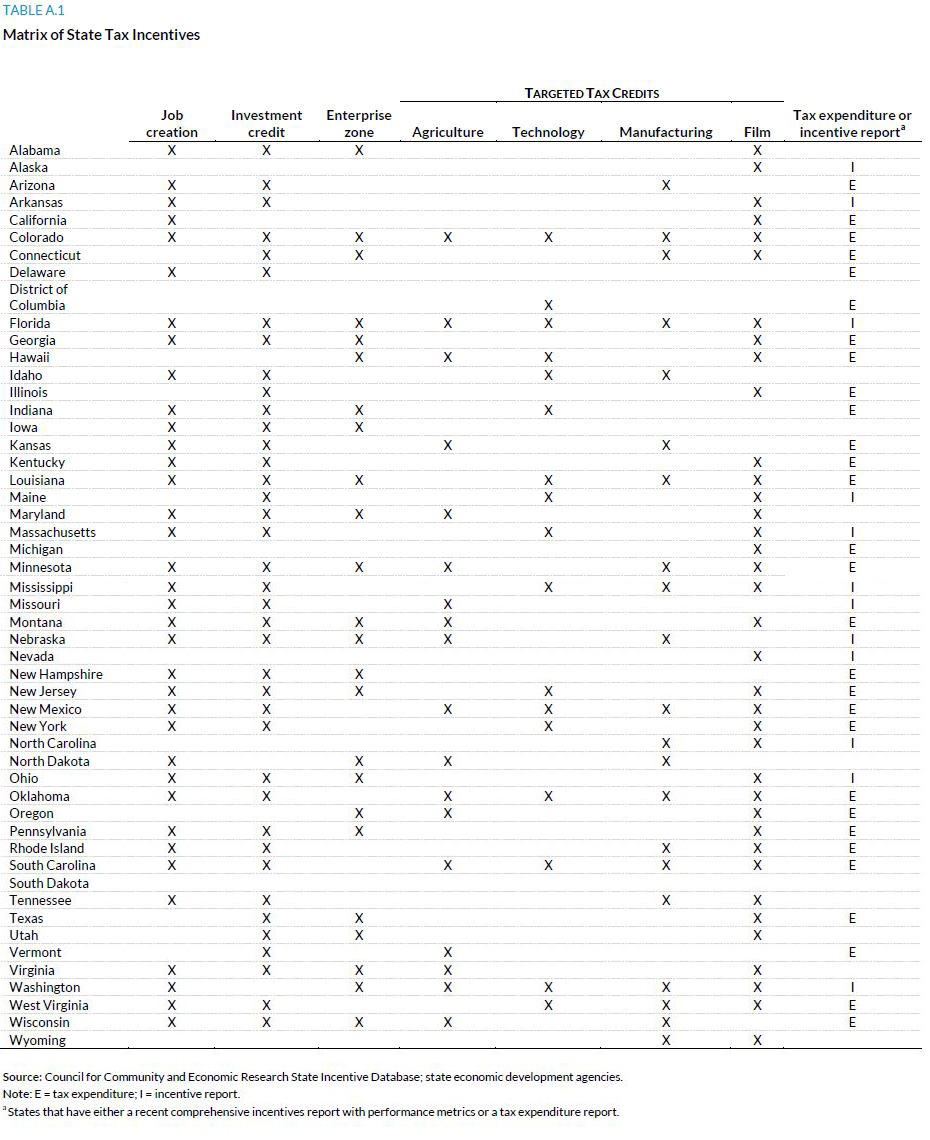

State tax incentives come in four basic types, focusing on jobs, business investment, specific industries, and specific locations. Variations in definition and target are considerable, however.

Jobs and Investment Tax Incentives

Tying incentives to job creation or capital investment enables states to tailor incentive programs to tangible goals. These credit types are available in virtually every state.2 The credits reward companies that either add new jobs or can verify that they retained jobs they otherwise would have cut. Some states use jobs as the unit of measurement; others use payroll. For example, Delaware’s job creation tax credit is $500 for each qualified new job, and Mississippi’s credit is equal to 2.5 percent of new payroll.

Other states have a stand-alone investment tax credit. These credits apply to a specific investment, usually expansion of facilities or purchase of new equipment. For example, Florida’s Capital Investment Tax Credit allows an investment credit of 5 percent annually for 20 years of eligible capital costs.3

Tax Incentives Targeted at Specific Industries

States also use tax incentives to promote specific industries. In some cases, the incentives are defensive, discouraging an existing local industry from leaving to collect incentives offered elsewhere. Incentives can also be proactive as states try to diversify their economies. The following industries are among the most common recipients of tax credits.

Agriculture

Incentives for agricultural activities across the states aim to preserve and promote farming and ranching. Some incentives attempt to help small farmers, such as Kansas’s credit for agritourism liability insurance and Nebraska’s credit for landlords who rent to beginning farmers. A few states use preferential excise tax rates or exemptions to develop wineries and breweries.

Technology

States often focus incentives on high technology, bioscience, and advanced manufacturing activities, hopeful that attracting these firms will enhance the state’s reputation as a technology hub like Silicon Valley in California; Austin, Texas; or North Carolina’s Research Triangle. These hubs attract high-paying jobs and highly educated employees and states see them as a way to diversify their economies. Twelve states and Washington, DC, provide high technology tax incentives; these range from a sales tax exemption for e-commerce in West Virginia to a comprehensive set of tax incentives for high technology companies in DC.

A subset of technology incentives targets the development of data centers. Nine states (Arizona, Minnesota, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington) encourage firms to create computer or Internet data centers, usually by offering reduced or no sales tax on computer servers and other equipment purchases or by exempting equipment from personal property taxes.

Manufacturing Incentives

States are particularly interested in attracting manufacturers that offer relatively high wages and benefits. In addition, large manufacturers such as automobile assembly plants often induce suppliers, particularly other manufacturers, to locate nearby. States most frequently offer job creation and investment credits to manufacturers, but many states also provide them abatements of both real and personal property taxes. West Virginia and Louisiana have state corporate income tax credits to offset local personal property taxes for manufacturers.

Some tax exemptions aim to reduce tax distortions and are not generally considered incentives. For example, 35 states offer sales and use tax exemptions for manufacturing machinery to prevent double taxation on transactions that involve intermediate goods or other inputs to production. However, for three states that target the exemption to new or expanding facilities, it becomes an incentive: Arkansas, Kentucky, and North Dakota have sales tax exemptions for machinery for new or expanding facilities (CCH Incorporated 2014).

Film Incentives

Over the past 15 years, 44 states have adopted targeted incentives for the film industry. Several states have structured the film credit as a refundable credit or rebate to film producers, unlike most tax incentives, which can only offset other taxes. These incentives vary from grants in DC and Georgia to fully refundable rebates in New Mexico. The credit is almost always refundable or transferable and exists even in states that have no income tax, such as Wyoming and Nevada, so film credits are essentially spending programs run through the tax code. Film incentives are controversial, sparking a debate about how to evaluate tax credits and economic activity (Tannenwald 2010). As a result, some states have recently repealed their film credits or capped the amount that could be awarded.4

Geographically Targed Tax Incentives

States either create or allow communities to designate zones, particularly in distressed communities, in which to encourage economic activity. The idea is that significant tax incentives will increase investment in a geographic area and thus lead to more jobs and a revitalized community.

Enterprise Zones

The most common zones are enterprise zones (also sometimes called empowerment zones). The federal, state, and local governments offer various incentives targeted at these zones to encourage economic activity in areas of high unemployment or declining property values. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development, for example, administered a grant program for states to establish empowerment zones with federal incentives for development, but authorization ended in 2014.5 The federal role has been sporadic, and many states have set up stand-alone programs. Colorado, for example, provides a variety of tax credits for investment and job creation in enterprise zones (Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade 2015).

Critics argue that companies that relocate into enterprise zones to take advantage of the incentives reduce their investment elsewhere (Papke 1993) and that the incentives are too small to drive location decisions (Peters and Fisher 2002).

Tax Increment Finance Districts

Most states have gone a step further with geographic preferences by establishing tax increment finance (TIF) districts. In these districts, often administered at the local level, the area’s tax revenue (or the increase in property tax revenues due to higher value) does not go into the general fund but rather remains with the district to pay off redevelopment costs or to pay for more investments. In most cases, local property taxes are diverted to the TIF district, but a few states, including New Mexico and Kentucky, have also allowed state sales taxes to be diverted.6

Other Zones

States have also experimented with giving incentives, ranging from tax breaks to financing assistance, to companies that locate in targeted zones, regardless of industry. Such support has financed industrial parks that have been adapted for high tech company incubation.

- Indiana’s Certified Technology Parks program is similar to a TIF district. The incentive is customized infrastructure financed by diverted tax revenue.7

- New York’s START-UP program allows universities to designate space (buildings and land) for new or expanding businesses. Companies that locate in a START-UP area receive significant tax benefits, including income tax abatements for employees.8 Other states have similar incubators at universities to facilitate the commercialization of research and patents.

- Virginia’s Defense Production Zone seeks to capitalize on federal defense spending, but only two communities have created the zones.9 Eligible companies can receive real property abatements as well as abatement of business, professional, and occupational license taxes.

Conclusion

Whether tax incentives achieve their goals of attracting and retaining business investment, they are not likely to disappear anytime soon. They are popular economic development tools even among low-tax states such as Nevada, which offers significant tax incentives even though the state does not have an income tax. Strategic planning can help states determine which industries they want to protect or attract with tax incentives to diversify their economies. But careful evaluation and monitoring is necessary to ensure that the incentives are achieving goals (see box 1). New requirements to report tax abatements in financial statements will help make some incentives more transparent, but comprehensive incentive reports are still important. Many states report tax expenditures, but few publish explicit reports on incentives that include performance measures.

-

“Site Selection Factors/Strategy.” Area Development, accessed January 19, 2016.

-

See “Job Creation Tax Credits – 50 State Table,” National Conference of State Legislatures, last modified 2013.

-

For a list of Florida incentives, see “Why Florida?: Incentives,” Enterprise Florida, accessed January 19, 2016.

-

Penelope Lemov, “Cut! States Are Walking Back Film Tax Credits,” Governing, September 11. 2014.

-

See US Department of Housing and Urban Development for the full list of empowerment zones. See also HUD (2013) for a summary of federal incentives available within empowerment zones.

-

See Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development (2015) for detailed information about TIF districts.

-

For details about certified technology parks, see “Indiana Certified Technology Parks,” Indiana Economic Development Corporation, accessed January 19, 2016.

-

See Startup NY for more information about university development areas in New York.

-

Loudoun County and the city of Manassas.

Arkansas Economic Development Commission. 2015. “Annual Activity Report for 2014 and Accounting of the Economic Development Incentive Quick Action Fund for FY2015.”

CCH Incorporated. 2014. State Tax Handbook 2015. Chicago: Wolters Klewer.

Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade. 2015. “Colorado Enterprise Zone Program Fact Sheet.” Denver: Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade.

Francis, Norton. 2015. “GASB 77: Reporting Rules on Tax Abatements.” Economic Development Strategies Information Brief 1. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

HUD (US Department of Housing and Urban Development). 2013. “Empowerment Zone Tax Incentives Summary Chart.” Washington, DC: HUD.

Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development. 2015. “Tax Increment Financing.” Frankfort: Kentucky Cabinet for Economic Development.

Lane, Brent, and G. Jason Jolley. 2009. “An Evaluation of North Carolina’s Economic Development Incentive Programs.” Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina.

Papke, Leslie E. 1993. “What Do We Know about Enterprise Zones?” In Tax Policy and the Economy, vol. 7, edited by James Poterba (37–72). Boston: MIT Press.

Peters, Alan H., and Peter S. Fisher. 2002. “The Effectiveness of State Enterprise Zones.” Employment Research 9 (4): 1–3.

Pew Charitable Trusts. 2015. “Tax Incentive Programs: Evaluate Today, Improve Tomorrow.” Economic Development Tax Incentives. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts.

Tannenwald, Robert. 2010. “State Film Subsidies: Not Much Bang for Too Many Bucks.” Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Appendix A

About the Economic Development Strategies Project

The Economic Development Strategies project is a three-year effort to assemble comprehensive research on state economic development strategies. The scope of the project goes beyond tax incentives (discussed here) to include workforce development and best practices. This is the third of eight informational briefs that will frame the project.

About the Author

Norton Francis is a senior research associate in the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute, where he works on the State and Local Finance Initiative. His current work focuses on state finances, economic development, and revenue forecasting. Francis has held senior economist positions in the District of Columbia and New Mexico, and has written about and presented on revenue estimating and state tax policy.

Acknowledgments

This brief was funded by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. We are grateful to them and to all our funders, who make it possible for Urban to advance its mission.

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or the insights and recommendations of Urban experts. Further information on the Urban Institute’s funding principles is available at www.urban.org/support.

The author gratefully acknowledges comments from Richard Auxier, Don Baylor, Donald Marron, Roberton Williams, and Kim Rueben as well as the Urban Institute communications team for careful layout and editing.