In less than 20 years, according to the latest official projections, Social Security will no longer be able to pay full benefits to retirees and people with disabilities. Yet, presidential candidates aren’t talking much about how they would fix the problem.

Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders want high-salaried workers to pay more Social Security taxes. A few Republicans, like Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and Marco Rubio, have proposed raising the retirement age and restricting benefits for high-income people to shore up Social Security. But 7 of the 12 Republicans who competed in the Iowa caucuses don’t offer any specific ideas on their websites about how to close the funding gap.

Republican candidate Mike Huckabee dropped out of the race after the Iowa caucuses this week. But during a debate last month, he offered a painless solution for Social Security: “Here's the fact. Four percent economic growth, we fully fund Social Security and Medicare. Our problem is not that Social Security is just too generous to seniors. It isn't. Our problem is that our politicians have not created the kind of policies that would bring economic growth.”

Some left-leaning commentators have made the same argument. Strong economic growth would raise earnings, which would boost payroll tax revenue going to Social Security, eliminating the need to cut benefits or raise taxes.

Is the solution really that easy? Unfortunately, it isn’t.

Four percent growth year after year is unrealistic. It’s been more than 40 years since we last completed even 10 years of 4 percent average annual growth (in inflation-adjusted dollars). And back in the early 1970s, the labor force was growing more than 2 percent a year as the baby boomers were coming of age and many women were entering the workplace. It’s going to be a lot harder to achieve that growth over the coming decades when the labor force is projected to increase only 0.5 percent a year.

But let’s say we could somehow turbocharge worker productivity enough to achieve average real economic growth of 3.4 percent a year indefinitely (and even higher rates in the short-term as we continue to recover from the Great Recession), instead of the 2.1 percent long-term rate that the Social Security trustees assume. This is optimistic, but it did happen between 1995 and 2005 (albeit when the labor force was growing more rapidly than today). Let’s assume that all of this additional growth results from higher productivity, instead of by expanding the labor force through more immigration or higher employment rates, and that it raises earnings uniformly for all workers.

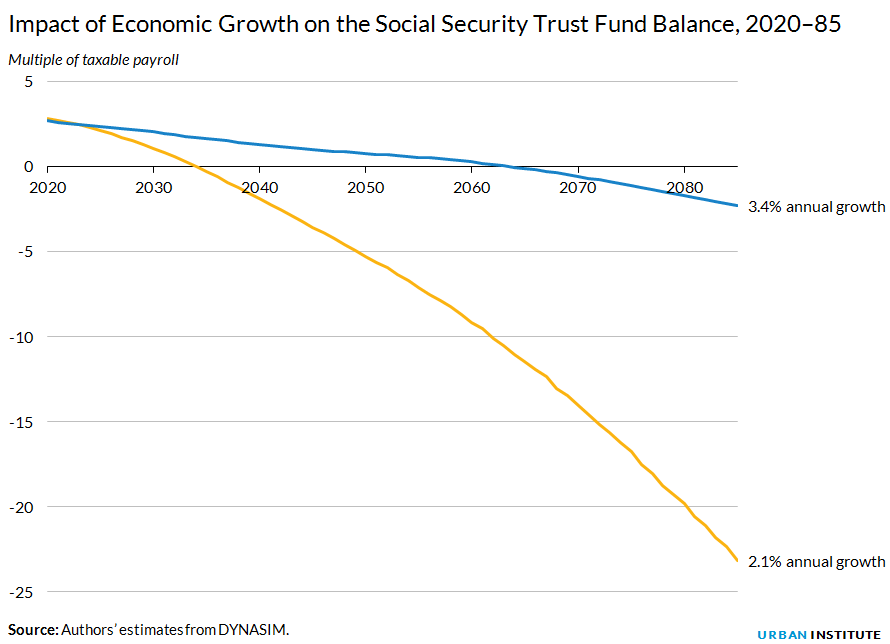

Crunching the numbers with DYNASIM, Urban Institute’s projection tool, we find that such economic growth would in fact significantly improve Social Security’s long-run balance sheet, pushing back by three decades the date when the system could no longer pay full benefits, from 2035 to 2064.

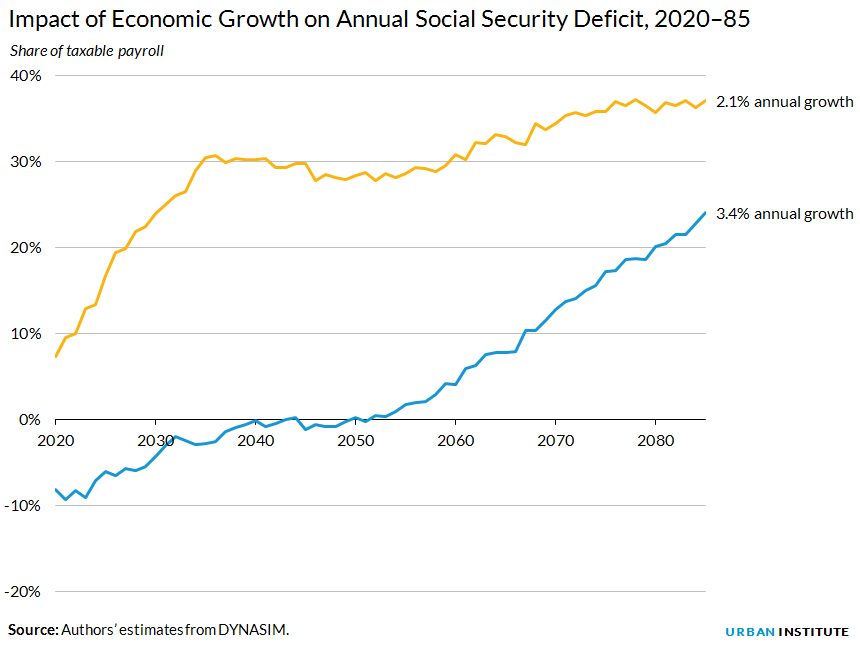

But those financial gains won’t last. Strong economic growth generates a lot of tax revenue for Social Security right away without immediately changing benefits. Over time, however, economic growth puts the system on the hook for much higher benefit payments. As the economy grows faster and people earn more, they eventually receive more Social Security benefits once they retire.

Under the high-growth scenario we considered, those higher benefits start squeezing Social Security by about 2050, when the system permanently begins owing beneficiaries more payments than it collects from taxes. That annual deficit then soars under the high-growth scenario as more retirees begin collecting sizable Social Security checks, growing much more rapidly than under the low-growth scenario. (These estimates compare annual tax receipts to scheduled benefits, not actual benefits, since Social Security would have to cut benefits paid each year to prevent the system from going broke.)

Faster economic growth, however implausible, might delay Social Security’s insolvency but won’t permanently solve the system’s financial woes. Instead, we’re going to have to make hard choices about raising taxes and cutting benefits. The presidential campaign is a good time to begin the debate.

Tune in and subscribe today.

The Urban Institute podcast, Evidence in Action, inspires changemakers to lead with evidence and act with equity. Cohosted by Urban President Sarah Rosen Wartell and Executive Vice President Kimberlyn Leary, every episode features in-depth discussions with experts and leaders on topics ranging from how to advance equity, to designing innovative solutions that achieve community impact, to what it means to practice evidence-based leadership.